Thermal cameras read the stress on my face

Victoria GilScience Correspondent, BBC News

When I was asked to give an impromptu five-minute speech and then count down in intervals of 17 – all in front of a panel of three strangers – acute stress registered on my face.

Indeed, psychologists from the University of Sussex filmed this somewhat terrifying experience for a research project that studies stress using thermal cameras.

Stress changes blood flow in the face, and scientists have found that the drop in temperature of a person’s nose can be used as a measure of stress levels and to monitor recovery.

Thermal imaging, according to the psychologists behind the study, could be a “game changer” in stress research.

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBCThe experimental stress test I underwent is carefully controlled and deliberately designed to be an unpleasant surprise. I arrived at university with no idea of what awaited me.

First, I was asked to sit, relax, and listen to white noise through headphones.

So far, it’s so calming.

Then the researcher conducting the test invited a panel of three strangers into the room. They all looked at me in silence as the researcher informed me that I now had three minutes to prepare a five-minute speech about my “dream job.”

As I felt the heat rising around my neck, the scientists captured my face changing color with their thermal camera. My nose quickly dropped in temperature – turning blue in the thermal image – as I considered how to navigate my way through this unanticipated presentation. (I decided to take the opportunity to make my pitch for joining the astronaut training program!)

The Sussex researchers carried out this same exercise test on 29 volunteers. In each of them, they saw their nose temperature drop between three and six degrees.

The temperature in my nose dropped two degrees, as my nervous system pushed blood flow from my nose to my eyes and ears – a physical response that helps me look and listen for danger.

Most participants, like me, recovered quickly; their noses warmed to prestress levels within minutes.

Lead researcher Professor Gillian Forrester explained that being a journalist and broadcaster probably got me used to being put in stressful positions.

“You’re used to the camera and talking with strangers, so you’re probably pretty resilient to social stressors,” she explained.

“But even someone like you, trained to deal with stressful situations, exhibits a biological change in blood flow, suggesting that this ‘nasal dip’ is a robust marker of a changing stress state.”

Kevin Church/BBC News

Kevin Church/BBC NewsStress is part of life. But according to scientists, this discovery could be used to help manage harmful levels of stress.

“The time it takes for a person to recover from this nasal depression could be an objective measure of how well a person regulates their stress,” Professor Forrester said.

“If they bounce back unusually slowly, could that be a risk marker for anxiety or depression? Is that something we can do something about?”

Since this technique is non-invasive and measures a physical response, it could also be useful for monitoring stress in babies or in people who are unable to communicate.

The second task of my stress assessment was, in my opinion, even worse than the first. I was asked to count down from 2023 in intervals of 17. A panel member of three impassive strangers stopped me every time I made a mistake and asked me to start again.

I admit that I’m bad at mental arithmetic.

As I spent an embarrassing amount of time trying to force my brain to subtract, all I could think about was that I wanted to escape the increasingly stuffy room.

During the investigation, only one of the 29 stress test volunteers actually asked to leave. The others, like me, completed their tasks – probably feeling varying degrees of humiliation – and were rewarded with another soothing session of white noise via headphones at the end.

Anxious monkeys

Professor Forrester will present this new method of measuring thermal stress to an audience at the New Scientist Live event in London on October 18.

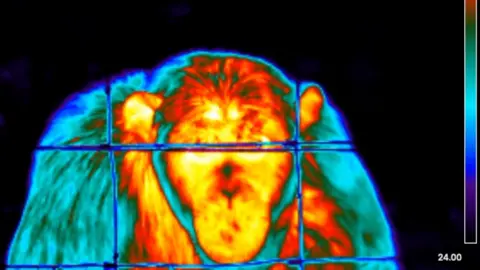

Perhaps one of the most surprising aspects of this approach is that because thermal cameras measure an innate physical stress response in many primates, they can also be used in non-human monkeys.

Researchers are currently developing its use in great ape sanctuaries, including chimpanzees and gorillas. They want to find ways to reduce stress and improve the well-being of animals that may have been rescued from traumatic circumstances.

The team has previously found that showing video footage of baby chimpanzees to adult chimpanzees had a calming effect. When the researchers set up a video screen near the rescued chimpanzees’ enclosure, they saw the noses of the animals watching the footage warm up.

So, in terms of stress, watching baby animals play is the opposite of a surprise job interview or an on-the-spot subtraction task.

Gilly Forrester/University of Sussex

Gilly Forrester/University of SussexThe use of thermal cameras in monkey sanctuaries could prove useful in helping rescued animals adapt and settle into a new social group and strange environment.

“They can’t say what they feel and they can hide what they feel very well,” said Marianne Paisley, a researcher at the University of Sussex who studies the welfare of great apes.

“We have [studied] primates for about 100 years to help us understand ourselves.

“Now we know so much about human mental health, so maybe we can use that and give back.”

So perhaps my own minor scientific ordeal might go some way towards alleviating the distress of some of our primate cousins.

Additional reporting by Kate Stephens. Photography by Kevin Church