The long-forgotten Batman Doppelgänger that most comic fans have never heard of

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

There was absolutely no way Bob Kane and Bill Finger knew what they were creating with Batman. The character debuted in 1939’s “Detective Comics” #27, in which he was a lone vigilante taking down criminals by any means necessary (even if that meant using guns, which he wouldn’t abandon until 1940). 85 years later, Batman is not only a box office icon with enduring star power, he has long since ascended to mythic status, becoming one of the few figures in pop culture deserving of “icon” status. But things would have been very different if audiences had resonated more with an eerily similar character who debuted the same year as Kane and Finger’s “strange figure of darkness.”

The story of this Batman lookalike actually begins in the pages of pulp magazines published six years before the Dark Knight’s debut. In 1933, Berryman Press published “Black Bat Detective Mysteries”, the first in a six-issue series written by Murray Leinster (aka William Fitzgerald Jenkins). He was a traveling detective who used a business card bearing the symbol of a bat. But this character had nothing to do with Batman and has never been cited as a direct influence (although pulp detectives certainly contributed to the creation of Batman more generally).

By the end of the ’30s, Finger and Kane’s creation was ready to descend, debuting in March 1939 as a costumed vigilante who used his bat-like appearance to strike fear into the hearts of criminals. But just four months later, another Bat-themed vigilante arrived in the form of the second Black Bat. This character was entirely distinct from the private eye of the 1933 pulps and bore several striking similarities to Batman, from his costume and modus operandi to an origin story similar to that of a certain Gotham City district attorney.

Black Bat could have been a clone of Batman

Part of what makes Batman such an appealing figure is how he combines aspects of all the hero archetypes that have come before him. From obvious influences such as Superman (who debuted in 1938) to the Lone Ranger and Zorro, Dick Tracy and pulp heroes such as The Shadow, Batman represents the ultimate combination of heroic tropes in all of fictional history. Even Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee ultimately influenced Batman’s story. As such, no one could ever argue that the Dark Knight was a complete ripoff of a single character. But a quick glance at history might initially suggest something similar.

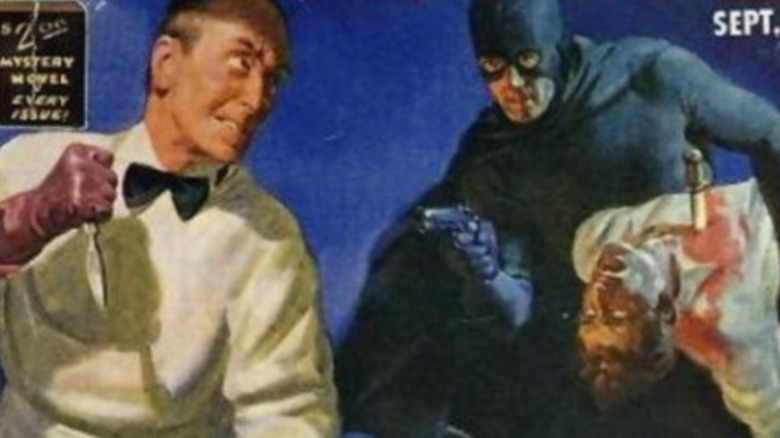

In July 1939, the second black bat arrived in “Black Book Detective” from Thrilling Publications (aka Better Publications, Inc.). Announced on the cover as a “mysterious enemy of crime”, the character occupied the same pulp space as his predecessor. As Mark Cotta Vaz says in his excellent “Tales of the Dark Knight: Batman’s First Fifty Years, 1939-1989,” Black Bat was “nearly identical to Batman.” This vigilante dressed in black, wore a coat designed to imitate bat wings and wore a black hood, all used to strike fear into the hearts of criminals. The first story, “Brand of the Black Bat”, was written by Norman A. Daniels under the pseudonym G. Wayman Jones, and saw lawyer Anthony Quinn and his alter ego Black Bat introduced as a “mysterious avenger” who “makes darkness his weapon”. Like Ben Affleck’s Batman in the old Snyderverse, the Black Bat also left bat-shaped stickers on his victims – although he didn’t follow Batfleck’s penchant for physically marking defeated criminals. The similarities don’t end there either.

Batman originally shared even more with Black Bat

In “Black Book Detective,” readers were given a story about Anthony Quinn and his character Black Bat. The lawyer was blinded when a criminal working for crime boss Oliver Snate threw acid in his face. Sound familiar? This should be the case, since a very similar fate befell Gotham District Attorney Harvey Dent (or Harvey Kent, as he was initially called) three years later, in 1943’s “Detective Comics” #66. Rather than being horribly disfigured, Quinn is blinded, only to regain his sight when another man’s corneas are grafted onto his own. The operation also gives Quinn the ability to see in the dark, which, combined with his newly enhanced senses he developed while blind, transforms him into a pulp superhero and an early predecessor to the equally powerful lawyer Matt Murdock/Daredevil.

At the time, Bob Kane claimed that his creation had nothing to do with the Black Book Detective hero (his original Batman sketch certainly suggests as much). But there were obvious parallels between the two, prompting threats of litigation that only dissipated when DC editor-in-chief Whitney Ellsworth intervened. One aspect that separated Black Bat from his DC counterpart, however, was the fact that the former didn’t hesitate to kill, attacking thugs left and right and often featuring these kills on the covers of “Black Book Detective.” Batman, on the other hand, has avoided such brutality. That is, he did it starting in 1940. By 1939, he was almost as deadly as Black Bat, throwing criminal Alfred Stryker into a vat of acid in “Detective Comics” #27 and even shooting down goons from an airplane in a later issue, before officially committing to his no-kill rule in 1940. Ultimately, the public chose Batman over Black Bat, but the latter lasted until the winter of 1953.