Scientists may have solved the mystery of Teotihuacan’s written language

The culture that flourished in Teotihuacan during the Classic period holds a unique place in Mesoamerican history. Today it is considered an emblem of Mexico’s national past and is one of the most visited archaeological sites in the Americas. Nevertheless, curious visitors learn that the ethnic and linguistic affiliation of the Teotihuacanos remains unknown. While the decipherment of other Mesoamerican writing systems has provided a wealth of information about dynasties and historical events, researchers have been unable to access information about Teotihuacan society from their own written sources. Indeed, the subject of writing at Teotihuacan raises several controversial questions. Do the signs of Teotihuacan imagery constitute writing? If it’s writing, how did it happen? Was it meant to be read regardless of language? If it represented a specific language, then what language was it? University of Copenhagen researchers Magnus Pharao Hansen and Christopher Helmke propose that Teotihuacan writing shared basic principles with other Mesoamerican scribal traditions, including the use of logograms according to the rebus principle, as well as a principle they call “double orthography.” Arguing that it encoded a specific and identifiable language, namely an Uto-Aztec language immediately ancestral to Nahuatl, Cora and Huichol, they propose new readings of several Teotihuacan glyphs.

A view of the small pyramids on the east side of Plaza de la Luna from the Piramide de la Luna towards the Piramide del Sol in Teotihuacan. Image credit: Daniel Case / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Teotihuacan is a sacred pre-Columbian city founded around 100 BCE and flourished until 600 CE.

Located in the northeast of the Basin of Mexico, the ancient city spanned 20 square kilometers, had a population of up to 125,000, and was in contact with other Mesoamerican civilizations.

It is not known who the builders of Teotihuacan were and what relationship they had with the peoples who followed. It is also unclear why the city was abandoned. There are several theories including a foreign invasion, civil war, ecological disaster or a combination of the three.

“There are many different cultures in Mexico. Some of them can be linked to specific archaeological cultures. But others are more uncertain. Teotihuacan is one of those places,” said Dr. Pharao Hansen.

“We don’t know what language they spoke or what later cultures they were related to.”

“A trained eye can easily distinguish Teotihuacan culture from other contemporary cultures,” Dr. Helmke added.

“For example, the ruins of Teotihuacan show that parts of the city were inhabited by the Mayans, a civilization much better known today than Teotihuacan.”

The ancient inhabitants of Teotihuacan left behind a series of signs, mainly in the form of murals and decorated pottery.

For years, researchers have debated whether these signs even constitute real written language.

The authors show that the writing on the walls of Teotihuacan is in fact the testimony of a language which is a linguistic ancestor of the Cora and Huichol languages and of the Aztec language Nahuatl.

The Aztecs are another famous culture of Mexico. Until now, the Aztecs were thought to have migrated to central Mexico after the fall of Teotihuacan.

However, researchers point to a linguistic connection between Teotihuacan and the Aztecs, which could indicate that Nahuatl-speaking populations arrived in the region much earlier and are actually direct descendants of the people of Teotihuacan.

In order to identify the linguistic similarities between the Teotihuacan language and other Mesoamerican languages, scientists had to reconstruct a much earlier version of Nahuatl.

“Otherwise, it would be a bit like trying to decipher the runes of the famous Danish runestones, like the Jelling Stone, using modern Danish. It would be anachronistic. You have to try to read the text using a language closer in time and more contemporary,” Dr Helmke said.

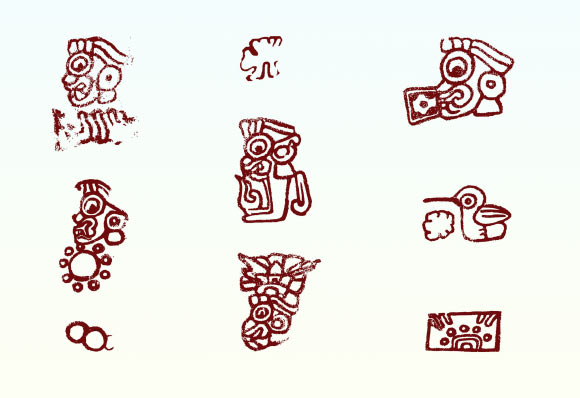

Examples of logograms that make up the written language of Teotihuacan. Image credit: Christophe Helmke, University of Copenhagen.

The written language of Teotihuacan is difficult to decipher for several reasons.

One reason is that the logograms that make up the script sometimes have a direct meaning, so that an image of a coyote, for example, should simply be understood to mean “coyote”.

Elsewhere in the text, the signs should be read as a sort of rebus, where the sounds of the objects depicted must be put together to form a word, which may be more conceptual and therefore difficult to write as a single figurative logogram.

It is therefore crucial to have a good knowledge of the Teotihuacan writing system and the Uto-Aztecan language, which these researchers believe is recorded in the texts.

Knowing how words sounded back then is necessary to solve the written riddles of Teotihuacan.

This is why the authors are working on several fronts. They simultaneously reconstructed the Uto-Aztec language, a difficult task in itself, and used this ancient language to decipher the Teotihuacan texts.

“In Teotihuacan, you can still find pottery with texts on it, and we know more murals will appear,” said Dr. Pharao Hansen.

“The fact that we do not have more texts clearly constitutes a limitation to our research.”

“It would be great if we could find the same signs used in the same way in many more contexts. »

“This would further support our hypothesis, but for now we have to work with the texts we have.”

Dr. Pharao Hansen and Dr. Helmke are excited about their discovery.

“No one before us has used an era-appropriate language to decipher this written language,” said Dr. Pharao Hansen.

“Nor has anyone been able to prove that certain logograms have a phonetic value that can be used in contexts other than the main meaning of the logogram.”

“In this way, we have created a method that can serve as a baseline that others can build on to expand their understanding of the texts. »

The team’s paper was published in the journal Current anthropology.

_____

Magnus Pharao Hansen and Christophe Helmke. 2025. The writing language of Teotihuacan. Current anthropology 66 (5); doi: 10.1086/737863