Rebecca Miller Wants You To Revisit Martin Scorsese’s Movies After Watching Her Apple TV “Film Portrait”

To hear Rebecca Miller tell it, Mr. Scorsese might not have happened the way that it did if the world hadn’t shut down. Previous attempts to document one of our era’s greatest filmmakers had been turned down, but Miller had Martin Scorsese in mind as the ideal subject for her next nonfiction screen project after completing 2017’s Arthur Miller: Writer, about her playwright father. With that seed of an idea growing, the biggest hurdle then became persuading Scorsese himself to participate in a documentary about his life and work. When the COVID-19 pandemic brought Hollywood largely to a halt, the resulting stoppage, according to Miller, gave the filmmaker more time to reflect than he would have normally allowed himself.

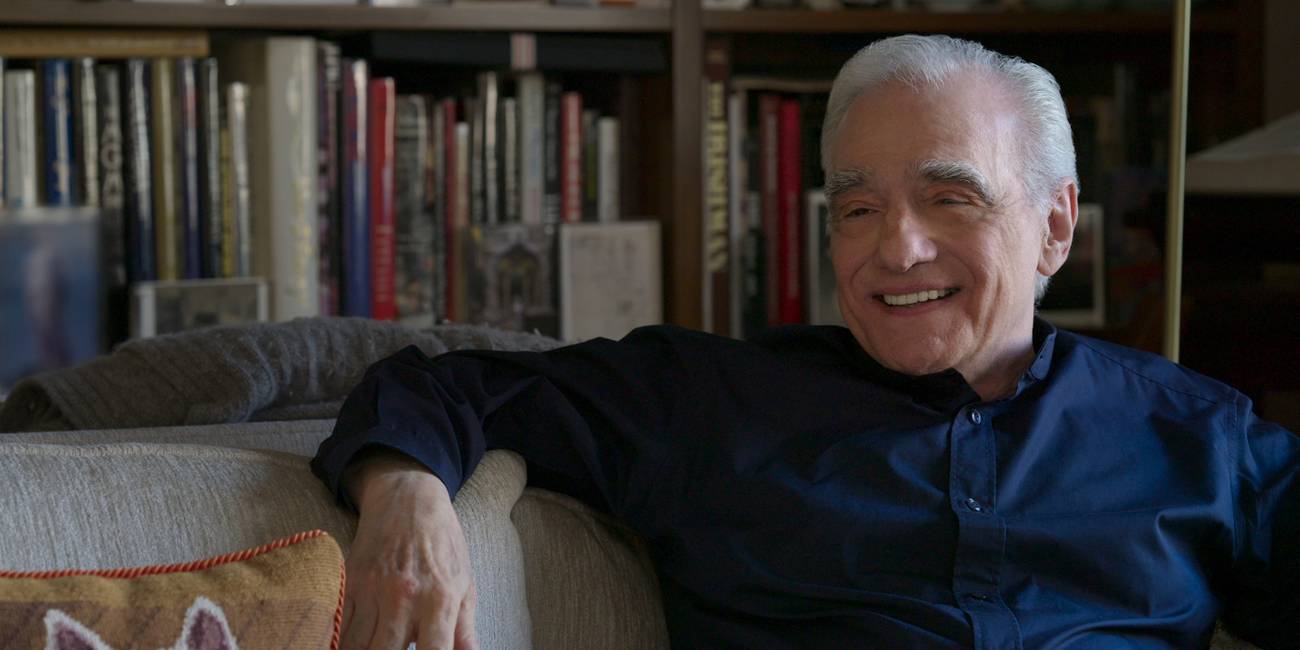

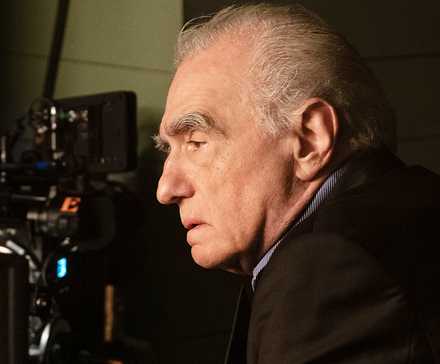

After a lengthy production and hours of interviews with Scorsese, as well as some of his closest friends, family members, and longtime collaborators, Apple TV is finally premiering Miller’s self-described five-episode “film portrait.” Ahead of its release on the streamer, the Mr. Scorsese director reflects on the process of making the docuseries, why it was initially intended as a feature film before expanding from the sheer wealth of knowledge, information, and access to Scorsese’s personal archives, which interviews she was most surprised to land, what she hopes viewers will ultimately take away from the experience, and much more.

COLLIDER: What was the genesis for this docuseries? How did it progress from idea to project?

REBECCA MILLER: It was really a notion. I was talking to my producing partner, Damon Cardasis. We had made Arthur Miller: Writer, another documentary, alongside Maggie’s Plan — not exactly the same time, but sort of alongside it, so that we were doing some of the research as we were getting ready to go for the other film, and I said, “I kind of like this process of having something on the boil as a documentary.” He said, “Well, what would your ideal subject be?” And I immediately said, “Martin Scorsese.”

I may have articulated it then, but I was really interested in his spiritual journey, which I thought was so interesting for somebody who’s so interested in and fascinated by violence — to have, also, this very intense spiritual journey. I had a sense that that was maybe integral to his whole body of work. I called his documentary producer, who I knew, who had helped us with the last documentary. I said, “I’m sure someone’s doing this.” It was Margaret Bodde, and she said, “No, actually, no one is making a big movie about Marty right now, because he won’t let anyone do it. Some people want to do it, but that’s a really interesting idea.” So she took it to him, and I wrote a letter, and then I met him, and one thing led to another. Here we are.

Why Martin Scorsese Finally Agreed to a Documentary About Himself

“It gave [him] a lot more time than he ever would have had, and I benefited from that.”

That’s another thing I’m curious about: Scorsese’s willingness to participate. Did it take a lot of convincing? Was he hesitant at first?

MILLER: He wasn’t so much hesitant, although I think he had been hesitant. I think this had been going on for a while, where people had been approaching him, perhaps. I don’t know the full story, but I think there were definitely people. How could there not be people? I think it may have been the right moment, or it may have been that he knew my work, already, pretty well. He had helped me back when I was going to make a film called Personal Velocity. I needed advice on films that used voiceover, and he gave me a few ideas, because I was on the set of Gangs of New York. That’s the only way I knew him, and it was not very well.

He gave me, of course, a lot of films to watch, as he would, and I asked him to look at the film. He looked at the film, and then he looked at my next film and my next film. I think he did it with three films, and so he was really aware of my work. He had seen, also, Arthur Miller: Writer, so he knew my attitude toward documentaries. He’d also read my books, as it turned out. He sort of knew me. It wasn’t like I was just coming out of nowhere when I said, “Would you like to do this?”

Also, weirdly, the pandemic happened right after my meeting with him. Even though, in the meeting, it started to sound like he was ready to do this, I think the pandemic shutting him down — you suddenly couldn’t make films — made him more introspective. It gave [him] a lot more time than he ever would have had, and I benefited from that. The first two interviews were outside, because of that.

Specifically, that opening interview, there’s that brief shot of you with the face shield on. It lends perspective to what a long-gestating project this was. How many interviews did you end up conducting with him over the course of the project?

MILLER: It was about five years altogether — maybe four-and-a-half years — that we were actually talking to each other. The first, actually, was two interviews outside. We had him in exactly the same chair in the same position, everything, so it looks like one. They were pretty long, about four hours each. Then, after that, I began to realize that this would be difficult to do as a feature, because he was only at 12 years old or something after eight hours. [Laughs]

Then we went to Sikelia, in his office, and we were allowed to go into his private offices, in his home. We did do one interview that was [over] Zoom interview. We didn’t use the video, but we have the audio, which was very, very good. It was a very good interview. Altogether, I think there are about 20 hours of interviews. In that interview, I noticed that there was no one else in the room, and he was so lucid. It felt so personal. I thought, “What about if we just get rid of the crew?” After that, I started getting the shots with a couple of cameras, and then I asked the crew to leave, and took the risk that sometimes the framing got weird or the lighting got weird, but it was worth it because we felt more alone.

Rebecca Miller Reveals the Most Surprising Interview She Conducted With Martin Scorsese

“… a long time later, he got in touch with me and said, ‘I have an idea.'”

Was there anything that came up for Scorsese, in looking back, that he maybe was surprised by or didn’t expect — like a memory that came out of nowhere, in reflecting on his childhood and the more formative years, things that maybe he hadn’t thought about in a long time?

MILLER: It’s a very interesting question. When he was talking about the expulsion from Corona, as he puts it, I asked him if his father had been humiliated by that, and he sort of answered yes, but without any elaboration. Then, maybe even a year later — it was a long time later; it could have been more than a year later. I had actually finished the interviews with him, so a long time later, he got in touch with me and said, “I have an idea.” So I went and did an audio interview with him, and he said, “You asked me if my father was humiliated, and I suddenly remembered that when I watched Bicycle Thieves for the first time, the memory of Corona came flooding back.” That’s why I use Bicycle Thieves, in that moment.

‘Mr. Scorsese’ Director Reveals How She Tapped Into the Legendary Filmmaker’s Past for New Documentary [Exclusive]

Scorsese has been nominated for 16 Oscars in his career.

I noticed that this is referred to as a “film portrait.” The obvious answer is you’re looking at him through his body of work, the films that we’ve all come to know and love — and, in some cases, are a little more controversial than others — but I was interested in hearing how you settled on that description.

MILLER: It’s a series, of course, but it’s also a portrait in that I wanted it to be clear that this was my portrait of him, which is different from “This is the ultimate filmography.” We do deal with 32 films. We do talk about, certainly, almost all of his feature films — we weren’t able to do every documentary or every television thing. The portrait implies that there’s somebody making the film, and I just wanted that to be clear, that I have a point of view, and I’m telling you that point of view. It’s not neutral, I guess, and that doesn’t mean it skews one way or the other way. I told the truth as best as I could.

You’ve just mentioned how much there was much more than could fit in a single feature-length documentary. How did you end up settling on five episodes? Was there more that you wanted to fit in but had to be cut out? Could it have been six?

MILLER: At first, yes, we thought it was a feature film, and that was how Apple came on board. Then David Bartner, the editor, and I brought the producers in, Cindy Tolan and David Cardasis, and we showed them what we had, what was to become the first episode. We were just like, “We don’t really think this is one film. We can’t do it. There’s just too much.” He’s done too much in his life, and there’s so much evidence. Because the films essentially are evidence for what you’re saying. It’s not like in the case of my other documentary, Arthur Miller: Writer. We’re talking about a writer. Writing doesn’t have that same thing, even playwriting. Watching plays on film is not as interesting as watching these wonderful films on film. It was just this plethora of stuff that we wanted to use.

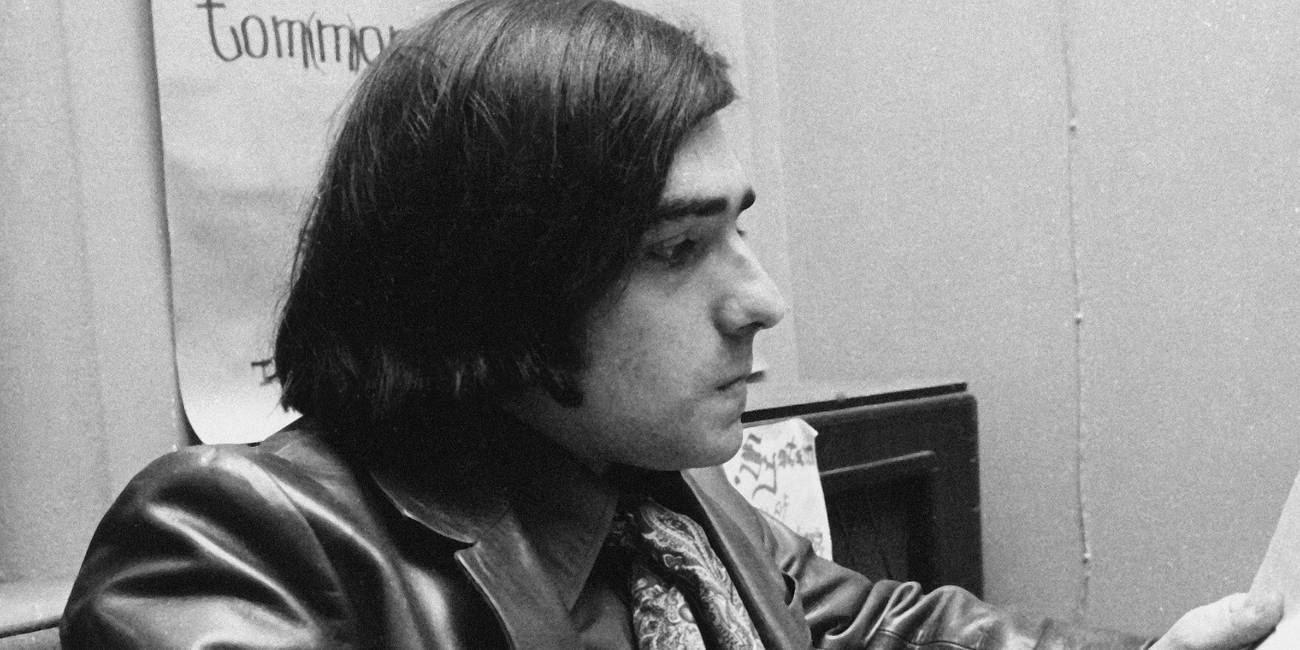

Anyway, they said, “Okay, it’s two episodes.” Then we got to two, and we were like, “Can you come back?” [Laughs] In the end, the first episode really is dedicated to essentially his childhood and the very beginnings of him as a filmmaker. Mean Streets is in Episode 2; [Robert] De Niro comes at the end of Episode 1. Because the film is basically the dance between the life and the work — the life creates the work, but the work creates life; you can’t really disentangle those two things, especially with Marty — there was that much story in his life for it. But what I really didn’t want was to end up with lists, because a lot of these movies about great whatever it is end up being, “And then he did this, and then he did this, and then he did this.” You end up overwhelmed by how much they accomplished, but without any real sense of how the work is knit into the person you know and how those two things are creating each other.

Rebecca Miller Explains Why ‘Mr. Scorsese’ Focuses on Specific Films

“It’s very interesting to experience that and peek into that other part of his life — which, in a way, is a very different Marty than we all feel that we know.”

There’s a lot of focus on the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s eras of his movies. I assume some of that was also a consequence of when this was made. At the end of it, we see him in pre-production on Killers of the Flower Moon, but did it just happen to be projects like Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, or Raging Bull that he was reflecting on the most?

MILLER: We do spend quite a lot of time on some of the later films, certainly, including then Leo [DiCaprio]’s films, and that’s already fairly early. But the truth is that the stories behind those films are so fascinating, and his life in that period.

What’s interesting, I was just thinking this the other day, is the way we know him now is so friendly and avuncular, and he’s this lovely character. It’s not that he wasn’t friendly, but he was a really dark and tormented person. It’s very interesting to experience that and peek into that other part of his life — which, in a way, is a very different Marty than we all feel that we know. It’s so interesting how people change. It’s like we’re witnessing him literally change before our eyes from the little boy who’s in love with church to then, suddenly, wants to be a priest, and then it goes on and on. I find it so interesting.

One of the moments that keenly stuck out to me while watching was the interviews with his daughters. The implication is that he was a very different father with each of them. One of the instances that says so much without needing to expand is when Domenica [Cameron-Scorsese] talks about working with him on Age of Innocence, and finally feeling the love that he has for his actors. Were there other moments like that that you found in the editing or the interviewing process — something revealing, and yet so human and vulnerable?

MILLER: Overall, I found myself a bit of an innocent when I came in. I really didn’t know that much about Marty’s personal life, his family. I knew the films. Every question to each person is just a genuine question, and I’m then following the breadcrumbs to the next question, like you do. I mean, that’s what you’re doing, right? It’s listening and response, essentially. You have to be totally awake.

At the end of some of my interviews with him, they were so exhausting that I couldn’t remember anything that happened, and I would have to ask the producers and then later look at it. I guess the answer is that I was constantly being surprised, and I do think that it does make a difference. It’s not that I wasn’t prepared, it’s just that, how would I be prepared? How would anybody be prepared? You’re just asking the questions and finding out. Because I didn’t have an ulterior motive, and I wasn’t trying to manipulate anything. I was really just asking questions and trying to get to know and make connections between elements of the work — trying to join up the dots, all the time.

In terms of interviewees, was there anybody you were most surprised said yes to participating?

MILLER: His friends, and Mick Jagger. [Laughs]

The former because so much of that was old history, and also some of it, at least in the case of one friend, was probably reflecting on some less-than-legal activity?

MILLER: Exactly! Nobody thought we were going to get him. I didn’t expect to. I didn’t go there thinking that we were, so that was a great moment. Also, just how genuine that was. I think one of my best ideas in the whole thing was the idea of getting him together with some of his friends, and you hear the dialogue. Today I did a radio thing, and you just hear them talking about that time where they were sticking the pencil into the guy’s head to see if it was a bullet hole. There’s something about just hearing that in audio that is really striking. He’s 12, and this is his experience of life. Hearing the voices, you see how real what he’s talking about is, how deep it is for him.

Rebecca Miller Reflects on Combing Through Martin Scorsese’s Personal Archives

“There’s nothing between his eye and you. He was taking pictures of his life, and there you are watching that.”

You were given what’s being described as “unprecedented access” to Scorsese’s archives. That footage of the interview with his parents just sitting on the couch is so lovely. There are so many little moments like that peppered throughout. How many of those gems did you unearth after you were already doing the interviews?

MILLER: It was a very, very long process. Of course, Sikelia was immensely helpful. And it was true that that happened gradually, partly because they had other things to do. They were working on Killers and all sorts of things, and so gradually we were getting stuff. They had to send for it in Rochester and then get it, and then something was missing, and they’d have to go back to Rochester because it’s this huge archive. But they were very, very generous.

He has an archivist, Marianne Bower, who was immensely helpful to us. She really became very important, almost like a wing of our own archivist, Allison Ferner, who is just a brilliant person. She had to find all sorts of things. David Bartner, the editor, was looking for things, and I was looking for everything. Yeah, it was immense. It was very deep, a deep treasure trove of stuff from Sikelia, from the world, from the web. And then sometimes tracking down people, like, “Who was the person who took those photographs?” so we can get permission because this was, sometimes, 40 years ago. That was not easy either.

Does anything specifically stand out in your mind from finding it in those archives?

MILLER: Oh, there were several of those. Footage of his family in the kitchen is pretty unbelievable. It’s like you’re right inside his kitchen when he was a kid, and there’s his family hanging out. That was pretty amazing. There’s a film called [Movies Are My Life], which David had found, and thank God we were able to get permission to use it, where he’s with Robbie Robertson in the middle of the night listening to music, and you just feel like you’re in there with them in that period of time doing whatever they’re doing. It’s a really amazing moment. And the Polaroids are so fantastic, from the Raging Bull period. That’s so personal. He was taking those Polaroids. There’s nothing between his eye and you. He was taking pictures of his life, and there you are watching that. That’s amazing.

What do you ultimately hope that people will take away from watching this?

MILLER: I think my real goal would be that they can go return to his films, and it would deepen the experience of watching them and the interpretation of them, [or] even return to them because some people haven’t watched some of the earlier films, or some of the films that weren’t the most famous. But even if they have, to return to them and maybe watch them in another way, give it another layer, an interpretation, or make them think about them in a different way. These films, you can read them almost endlessly. You can experience them and then every time you watch them, you’ll get something else out of them. This film is really for that, I think. It’s about a deepening of the reading of his films.

All episodes of Mr. Scorsese are now streaming on Apple TV.