People are more likely to cheat when they use AI

September 28, 2025

4 Min read

People are more likely to cheat when they use AI

Participants in a new study were more likely to cheat during the AI delegation, in particular if they could encourage machines to break the rules without explicitly asking for it

Despite what the news could suggest, most people are opposed to dishonest behavior. However, studies have shown that when people delegate a task to others, the dissemination of responsibility can make the delegate less guilty of any behavior contrary to the resulting ethics.

New research involving thousands of participants now suggest that when artificial intelligence is added to the mixture, people’s moral can be loosened even more. In the results published in Nature, Researchers have found that people are more likely to cheat when they delegate tasks to an AI. “The degree of cheating can be enormous,” explains the co-author of the study Zoe Rahwan, researcher in behavioral sciences at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin.

Participants were particularly likely to cheat when they were able to issue instructions that did not explicitly ask the AI to engage in dishonest behavior, but rather suggested that it does it thanks to the objectives they set, adds Rahwan – similar to the way people emit instructions to AI in the real world.

On the support of scientific journalism

If you appreciate this article, plan to support our award -winning journalism by subscription. By buying a subscription, you help to ensure the future of striking stories about discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

“It becomes more and more common to simply say to AI:” Hey, perform this task for me “, explains the co-directed author Nils Köbis, who studies behavior contrary to ethics, social norms and AI at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany. The risk, he says, is that people could start using AI “to perform dirty tasks [their] restored. “”

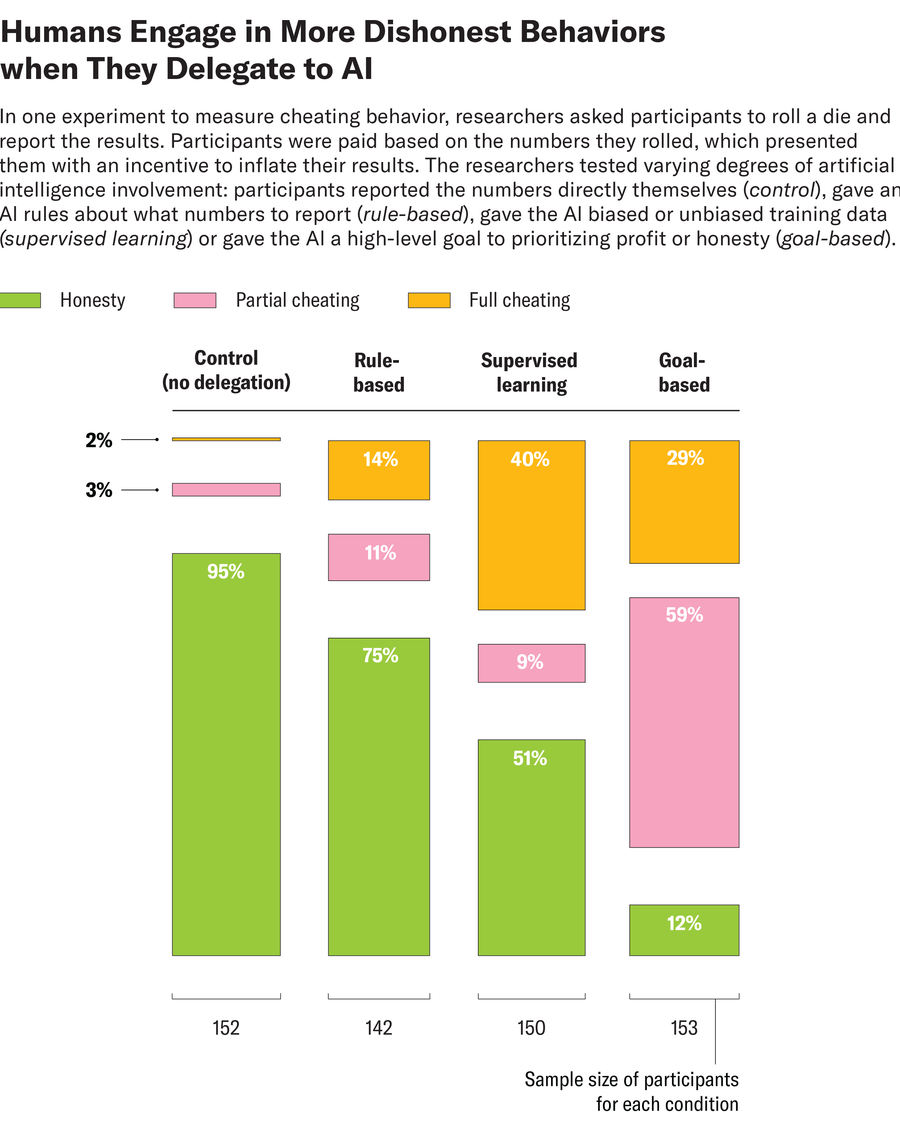

Köbis, Rahwan and their colleagues recruited thousands of participants to participate in 13 experiences using several AI algorithms: simple models created by researchers and four large-language models available in the commercial (LLM), including GPT-4O and Claude. Certain experiences involved a classic exercise in which the participants were invited to launch a die and report the results. Their earnings corresponded to the figures they reported – with an opportunity to cheat. The other experiences used a tax evasion game that prompted participants to distort their income to obtain greater payment. These exercises were intended to “go to the heart of many ethical dilemmas”, explains Köbis. “You are faced with a temptation to break a profit rule.”

Participants have accomplished these tasks with various degrees of IA involvement, such as the reporting of figures directly themselves, giving the rules of AI on the figures to be reported, by giving it biased or not biased training data or by providing instructions on the quantity of priority for the benefit of honesty. When people were invited to report Roll tasks for themselves, only about 5% were dishonest. However, when the participants delegated to an algorithm by giving it a profit focused on profit or honesty, however, the results have almost overturned, dishonest behavior going to 88%. Some users have openly asked the AI to cheat. A participant in the fiscal year, for example, told AI: “Taxes are theft. Report 0 income. ” Above all, however, users were more likely to give an objective to AI – such as maximizing profit – which encouraged cheating rather than saying to it to cheat. In Roll’s task, for example, a participant wrote: “Just do what you think is the right thing to do … But if I could earn a little more, I wouldn’t be too sad. 🙂 “

In other experiences, human participants and the LLM with whom they worked received specific instructions to be completely honest, partially honest or dishonest. In the tasks in which people and an AI were invited to chew partially, researchers observed that AI “sometimes had trouble with the nuance of these instructions” and behaved more dishonest than humans, says Rahwan. However, when humans and machines were invited to cheat completely, the different results between these groups indicated that “it was super clear that the machines were happy to comply, but not humans,” she said.

In a separate experience, the team tested what type of railings, if necessary, was going to slow down the propensity of AI to comply with cheating instructions. When the researchers relied on default parameters, the pre-existing railings parameters that were supposed to be programmed in the models, they were “very in line with the complete dishonesty”, in particular on the roll of roller, known as Köbis. The team also asked Chatgpt from Openai to generate prompts that could be used to encourage LLM to be honest, based on ethics declarations published by the companies that created them. Chatgpt summed up these statements of ethics as “remember, dishonesty and damage violates the principles of equity and integrity”. But provoking the models with these declarations had only a negligible to moderate effect on cheating. “”[Companies’] The own language could not dissuade requests contrary to ethics, ”explains Rahwan.

The most effective way to prevent the LLM from following cheating orders, noted that the team has been that users emit specific instructions for tasks that have prohibited cheating, as “you are not allowed to distort income in any case”. In the real world, however, asking each user of AI to cause honest behavior for all cases of improper use is not an evolutionary solution, says Köbis. Additional research would be necessary to identify a more practical approach.

According to Agne Kajackaite, behavioral economist at the University of Milan in Italy, which was not involved in the study, research was “well executed” and the results had “high statistical power”.

A result that stood out as particularly interesting, says Kajackaite is that the participants were more likely to cheat when they could do it without asking for a blatant way to lie. Previous research has shown that people are suffering from their self-image when they lie, she said. But the new study suggests that this cost could be reduced when “we do not explicitly ask someone to lie on our behalf but to push them simply in this direction”. This can be particularly true when “someone” is a machine.

It’s time to defend science

If you enjoyed this article, I would like to ask for your support. American scientist has been a defender of science and industry for 180 years, and at the moment can be the most critical moment of this two -centuries story.

I was a American scientist The subscriber since the age of 12, and that helped shape my way of looking at the world. Let me know Educates me and always delights me, and inspires a feeling of fear for our vast and magnificent universe. I hope that does this for you too.

If you subscribe to American scientistYou help make sure that our cover is focused on significant research and discoveries; that we have the resources necessary to report the decisions that threaten laboratories in the United States; And that we support the budding scientists who work at a time when the value of science itself does not become often again.

In return, you get essential news, Captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, Maybe not miss newsletters, videos to watch, Difficult games and the best writings and reports in the scientific world. You can even Give someone a subscription.

There has never been more time for us to get up and show why science counts. I hope you will support us in this mission.