Paul Thomas Anderson’s Wild American Epic

Books & the Arts

/

September 25, 2025

One Battle After Another, a sensational adaptation of a Thomas Pynchon novel, captures the manic energies of a country on the brink.

Let’s get this out of the way: One Battle After Another, the new Leonardo DiCaprio–starring blockbuster from Paul Thomas Anderson, is a Thomas Pynchon adaptation. It is not his first foray into Pynchon—the writer-director’s Inherent Vice (2014) was a literal restaging of the author’s beach-noir detective yarn—but this new one feels, somehow, even truer to the novelist’s spirit.

From Pynchon’s 1990 novel Vineland, Anderson borrows a basic conceit: A group of countercultural misfits, living underground, whose lives-on-the-fringe are disturbed by the return, years later, by a government tormentor operating as a stand-in for that all-American avatar of authority and oppression typically called “The Man.” Pynchon’s book toggles between the 1960s (when student radicals form a breakaway state on the coast of California, dedicated to the sacraments of surfing and rock ’n’ roll) and the Reagan-era ’80s, when most of that excitable energy had either sold out, or burned out. Anderson brings the idea to the present moment, with an activist group called the French 75, whose agitations are a little less freewheeling. They liberate immigrant holding camps on the border. They bomb government buildings. They intimidate politicians threatening abortion access.

When one job goes south, the French 75’s de facto leader, Perfidia Beverley Hills (Teyana Taylor), betrays her comrades, and shacks up with the grimacing anti-immigration military strongman Stephen J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn). Racked by guilt, she squirrels out of Witness Protection and absconds to Mexico, leaving him to sneer over a particularly evocative “Dear John” letter. With the French 75 dismantled (and many members summarily executed), Perfidia’s former main squeeze (DiCaprio) takes their daughter—who may in fact be Lockjaw’s daughter—and decamps underground, with the two adopting the aliases of Bob and Willa Ferguson.

Sixteen years later, Willa, played with tenderness and ferocity by Chase Infiniti, is (almost) all grown-up. Just in time for Lockjaw and his goons to launch a raid against the tiny, mostly Latino sanctuary city of Baktan Cross (the movie’s version of Pynchon’s NorCal hippie enclave of Vineland). The stated mission: a raid on a migrant-staffed chicken nugget factory that may be a heroin manufacturing operation. Lockjaw’s personal orders to his men: to capture Willa, and “bag-and-tag” Bob. Another French 75 member, Deandra (Regina Hall), also reemerges from the woodwork, to spirit Willa to safety. Meanwhile, Bob has to evade capture (and worse), reimmerse himself in the radical milieu, and stay (somewhat) sober long enough to find Willa.

At first blush, Vineland seemed unadaptable in a contemporary context. Not only because of the density of the prose or the lunacy of its plot—which includes a Godzilla attack, a UFO, and a tow truck that ferries the spirits of the damned to hell—but because of its chronology. The commodification of the restless hippie spirit in the Reagan age was the book’s subject. Porting the story over to an era where both flower children and Reaganites seem like little more than Halloween costumes seemed, frankly, like a bit of a category mistake. But Anderson’s film proves that these more central divisions—between freaks and squares, parents and children, the rigid brokers of authority and subversive agents of liberation—can be mapped across American history. Or as Perfida says in a voiceover, marking the time film’s smash cut into the present: “16 years later, the world has changed very little.” Make it 30. Or 70.

Beyond the basic story beats and main characters (the names have changed, but the personalities have clear analogs in Vineland) Anderson also taps into a fundamental tension of Pynchon’s book. Perfidia’s betrayal is as much political as it is personal, driven by her unaccountable fixation with Lockjaw’s hard-ass authoritarianism.

Current Issue

At their first meeting, she holds him up with his own service weapon, and demands that he get an erection. Later, during a hotel tryst, she points that same firearm to more penetrative ends. There is, if not quite a mutual respect between enemies, something no less energizing, and lethal coursing between Perfidia and Lockjaw. It’s an erotic charge borne of crisscrossing currents of perverse fascination and total contempt; the flirtation crosses lines of class, race, power, and basic allegiance. Pynchon has identified a similar dynamic animating so much of human psychology in the nuclear age. It’s the essence of Gravity’s Rainbow’s recurring comparison between WWII-era V2 rockets and its protagonist’s sexual proclivities, and the proto-Nazi bacchanalias unfurling in his new novel, Shadow Ticket. For all their superficial wackiness, his novels chronicle the contemporary fetish for transgression, self-destruction, and for the suffocating smother of death itself.

Of course, death itself is a formidable foe. And it finds its counterbalance in the radical energies of the underground. By the time of Lockjaw’s return, Bob has sunk deep into a ne’er-do-well lifestyle of pot-smoking, drunk driving, and rank paranoia. Once a devout revolutionary (and gifted incendiary expert), Bob has fizzled into another familiar Pynchonian archetype: the affable wastoid barely getting by on his own wits. When the shit hits the fan, and Bob has to spring to action to save his daughter, he’s caught totally flat-footed: He’s always half-a-step behind, even if his heart is squarely in the right place.

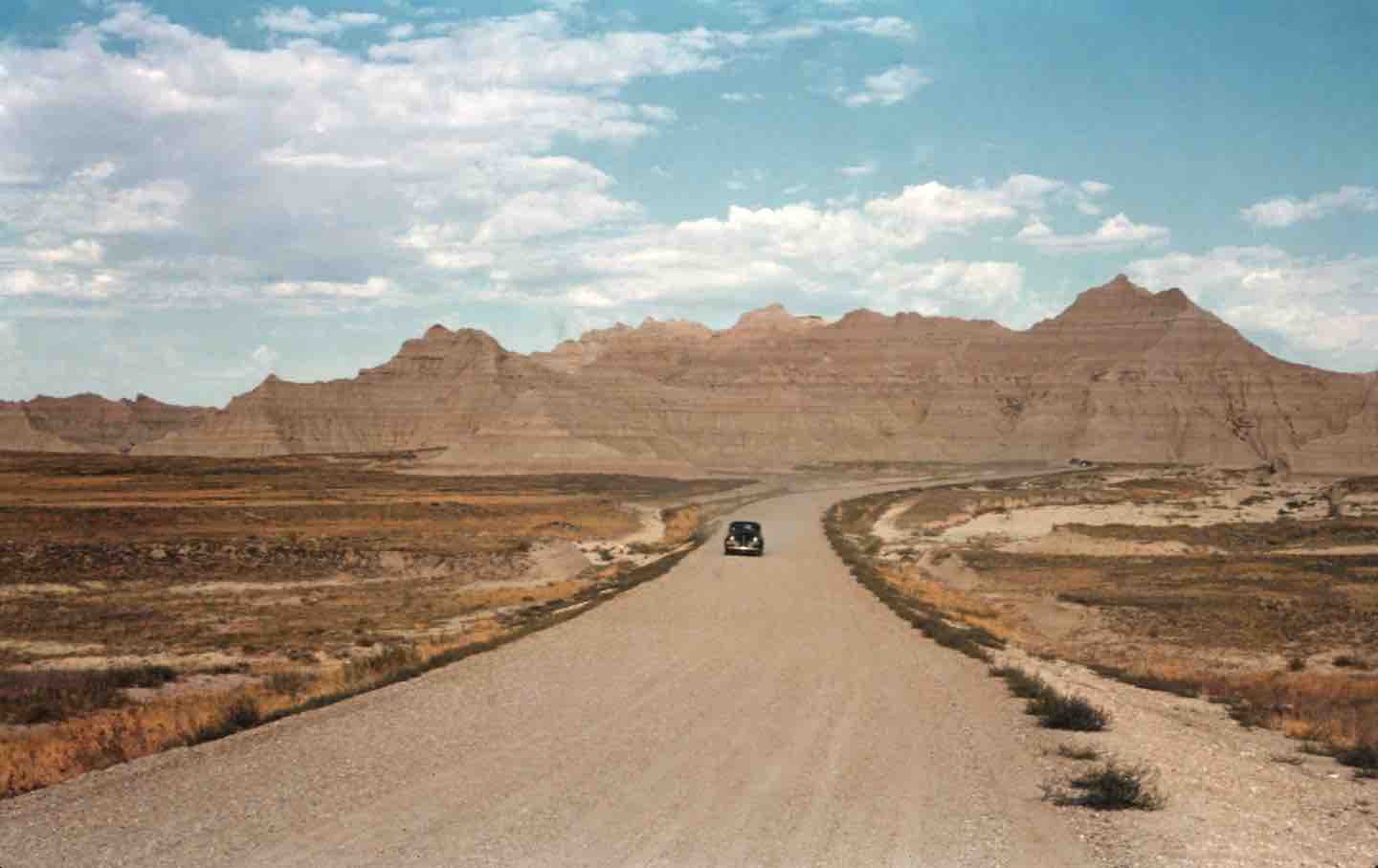

DiCaprio plays it as a mongrel spawn of Stallone’s aggrieved, industrious vet John Rambo, and Jeff Bridges’s harried “Dude” from The Big Lebowski. He’s a half-baked guerrilla with a hair-trigger temper. Aided by a local karate teacher (Benicio del Toro), Bob trails his daughter’s pursuers: through a rioting Baktan Cross, across the desert to a hidden convent staffed with heavily armed super-nuns, and finally bobbing up and down long stretches of sun-soaked highways, in a climatic—and visually arresting—chase sequence. Like the stock Pynchon hero, he is hapless but more or less capable; a well-meaning stooge who survives on his wits, flies by the seat of his pants (or threadbare bathrobe), and gets by with a little help from his friends.

Bob’s quest to find his daughter runs parallel to Willa’s confrontation with her muddled family history. It’s not only that Lockjaw may be her dad and that Bob is just, well, some guy. It’s that Bob had lied to her about her mother. Willa grew up believing Perfidia was a noble hero, downed in battle, not a snitch who sold out her cause to save her own skin. Her adolescent conception of herself, as the daughter of two valiant partisans, is thrown into disarray, as she reckons with the reality of being the child of both a traitor to the cause and the cause’s chief nemesis.

Despite the driving Jonny Greenwood score, the sumptuous cinematography, and tremendously calibrated performances (Penn is especially good; his rep as a definitive “Hollywood liberal” adding considerable fission to his turn as an authoritarian gargoyle), One Battle After Another feels almost completely unlike anything in Paul Thomas Anderson’s filmography. Films like There Will Be Blood (2007), The Master (2012), and Phantom Thread (2017) are imposing, idiosyncratic works of a director who seemed increasingly in control of his considerable talents. One Battle After Another is perhaps the director’ s most conspicuously entertaining film since 1997’s Boogie Nights: full of humor, brio, and expertly executed car chases and shoot-outs. Despite its nearly three hours, it is an incredibly brisk and lean film. (It’s also the only major studio awards contender in recent memory to see a character described as a “semen demon.”)

It is Anderson’s biggest, most expensive work. And it arrives on the eddies of a relentless PR campaign: glossy magazine profiles, widely-mocked social media memes, Peyton Manning tie-in ads airing during ESPN’s Monday Night Football broadcast, and even a promotion in the video game Fortnite. It is admittedly a bit weird to see a “PTA” film pitched like this. Anderson’s films have long been marked by what the critic Nick Pinkerton described as “a series of uneasy negotiations between the multiplex and the art house.” Here, he embraces all those latent (even suppressed) blockbuster tendencies. As a filmmaker who has made a career striving for—and often achieving—grandiosity, the scale suits him. But neither the needling marketing schtick nor the movie’s status as a capital-e Entertainment diminishes its depth. Quite the contrary.

If the bullet points—immigrant detention facilities, abortion access, white supremacists—didn’t make it obvious, this is a movie with a great deal on its mind. Some of the film’s details may seem searingly, even comically, relevant at the present time: from a customer service representative at a call center for radicals who grumbles about “triggers,” to the military dispatching a black-clad “antifa” thug to raise the temperature at a riot. These gags may well end up dating One Battle After Another. But it’s less about shameless zeitgeist-baiting and more about the ripped-from-the-headlines bits making the story seem both of our time, and any.

Indeed, the fray between Willa’s dueling would-be dads, and her feelings about her absentee mother, have less to do with issues of mere paternity or heredity. It’s a common observation (or gripe) that Pynchon’s characters operate more as embodiments of certain ideas, or postures, either exemplifying (or floundering between) competing political, cultural, and philosophical extremes. Anderson, too, has long been preoccupied with such bedeviled personalities. His heroes, from Dirk Diggler in Boogie Nights to the petrol heir H.W. Plainview in There Will Be Blood, to the inscrutable and tragic Freddie Quell in The Master, drift between dueling influences, and scrambling to define their own identities, inside or outside of their sway.

Willa is an exemplar of this type: part reformer, part dropout, part tyrant, part narc. Everything about her, from her multiracial background to her get-up (leather jacket over a white T-shirt, with a mismatching tutu) suggests her contended, subjunctive status. Like Rocky Balboa or Jay Gatsby before her, Willa is America: in the seam of the starry-eyed solidarity of revolution, and the death-drive of authoritarianism, between ideological poles Pynchon himself once described as “the hothouse of the past” and “dreamscape of the future.”

Pynchon has long shunned explicit ideological commitments. Or, at the very least, he has proved extremely coy regarding his own. (He is “extremely coy” about most everything, at least publicly.) Vineland is subtle, and nuanced, because the author accounts for the seductive allure of the authoritarian impulse. Anderson is altogether less skittish—trading in his usual ambiguity for brute force impact.

After the initial sexual tension between Perfidia and Lockjaw dissipates, the film’s knotty politics disentangle, too. Lockjaw, with his granite visage and sinewy biceps, presents an obvious show of strength. But Bob and the remnants of the French 75 model a different, more compassionate display of force. One Battle After Another offers up a fantasy of revolutionary esprit de corps, where every ex-radical, migrant laborer, longhair, stoner, sympathetic social worker, and skateboarding punk is part of an expansive underground movement. It is a vision of a cohesive American revolutionary left that may only actually exist in the paranoid Republican mind.

The idea of the “found” or “chosen” family has become something of a cliché. But the idea’s overfamiliarity should not discredit the idea (or trope) itself. One Battle After Another is very much a film about families of choice, and bonds born not of blood (or the deluded belief in racial or nativist dominion) but of shared affiliation, ambition, and fellow-feeling. It validates the vision of America as a patchwork, and hodgepodge, not some fiery smelt where difference and particularity are dissolved. Anderson’s exploration of big ideas of race and power is deft and bracing. The dirty work of revolution, according to this film, need not be so grim and self-serious; it can involve excitement, and sex appeal, and the pleasure of ripping around on skateboards and slamming Modelos with like-minded comrades. It is a joy to watch.

Without hectoring or haranguing, One Battle After Another also throws its concerns back at the audience, asking them to take seriously the question of how a person, or a nation, should be. As Lockjaw scowls, staring down Willa as they tensely await the results of a paternity test, her fate, like that of the imperfect union she represents, hanging in the balance: “It’s your future.”

Don’t let JD Vance silence our independent journalism

On September 15, Vice President JD Vance attacked The Nation while hosting The Charlie Kirk Show.

In a clip seen millions of times, Vance singled out The Nation in a dog whistle to his far-right followers. Predictably, a torrent of abuse followed.

Throughout our 160 years of publishing fierce, independent journalism, we’ve operated with the belief that dissent is the highest form of patriotism. We’ve been criticized by both Democratic and Republican officeholders—and we’re pleased that the White House is reading The Nation. As long as Vance is free to criticize us and we are free to criticize him, the American experiment will continue as it should.

To correct the record on Vance’s false claims about the source of our funding: The Nation is proudly reader-supported by progressives like you who support independent journalism and won’t be intimidated by those in power.

Vance and Trump administration officials also laid out their plans for widespread repression against progressive groups. Instead of calling for national healing, the administration is using Kirk’s death as pretext for a concerted attack on Trump’s enemies on the left.

Now we know The Nation is front and center on their minds.

Your support today will make our critical work possible in the months and years ahead. If you believe in the First Amendment right to maintain a free and independent press, please donate today.

With gratitude,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

The writer’s only novel, “Tramps Like Us”, is a classic of queer literature—one that crystallizes the agony and the ecstasy of coming of age during the HIV era.

Books & the Arts

/

Sasha Geffen

Former Disney CEO Michael Eisner berated the company’s capitulation before authoritarian MAGA threats, but in many ways, he set the example.

Ben Schwartz

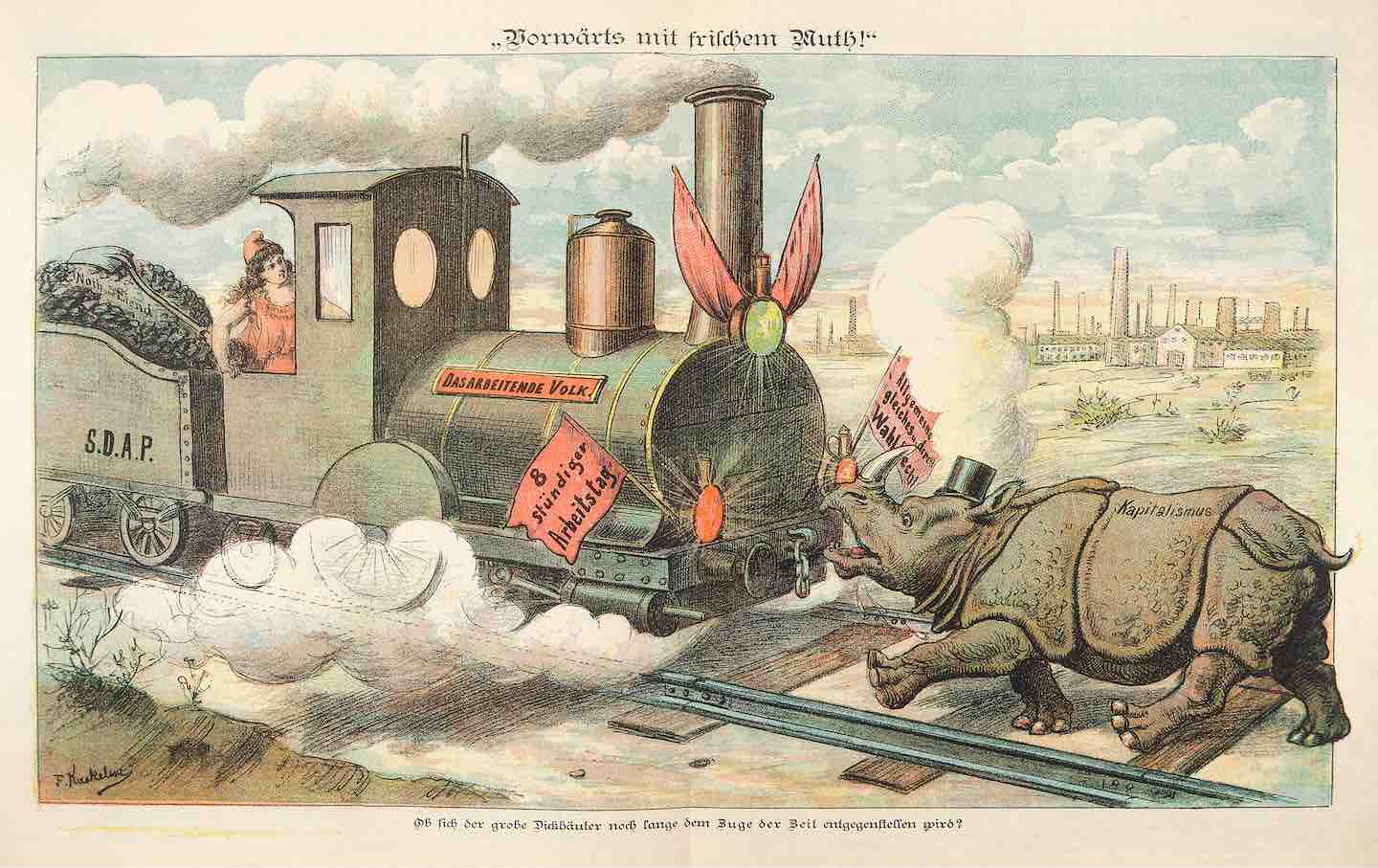

According to John Cassidy’s century-spanning history “Capitalism and Its Critics”, the system lives on because of its antagonists.

Books & the Arts

/

Erik Baker

A conversation with Thea Riofrancos about her new book “Extraction” and the hidden cost and obscured history of the capitalist push to monetize the energy transition.

Books & the Arts

/

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

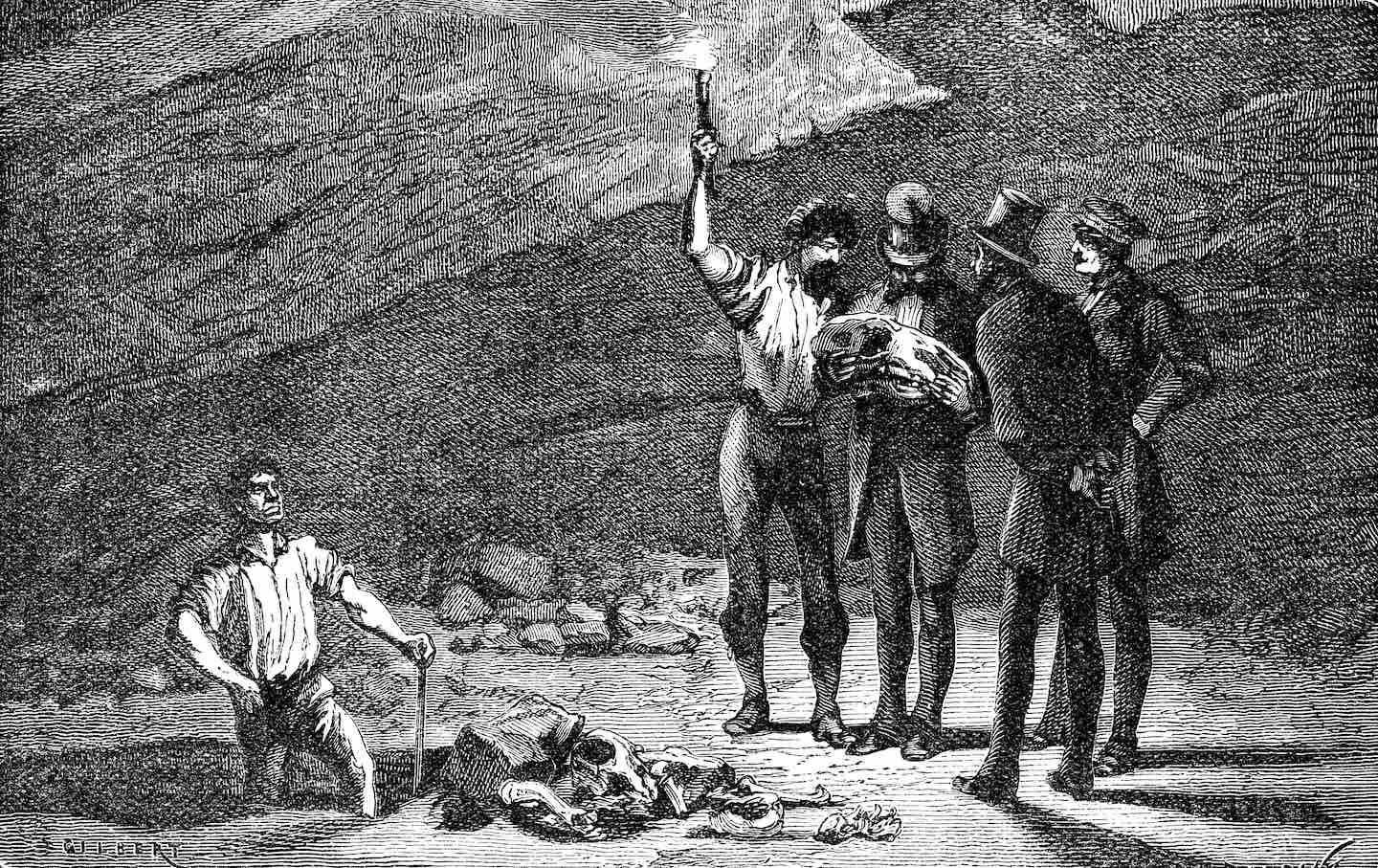

When the remains of prehistoric creatures were discovered in Europe and the United States, it opened up a vociferous debate on the nature of time and the purpose of science.

Books & the Arts

/

Andrew Katzenstein

Karen Hao’s recent book on the company argues that its ambitions are not merely about scale or the market but the creation of a global force that rivals a colonial power of old.

Books & the Arts

/

Andrew Deck