On the Road With Joe Westmoreland

Books & the Arts

/

September 25, 2025

The writer’s only novel, Tramps Like Us, is a classic of queer literature—one that crystallizes the agony and the ecstasy of coming of age during the HIV era.

A 35mm film photo shows an automobile making its way down an empty dirt road in Badlands National Park, 1940.

(Courtesy of the Jim Heimann Collection/Getty Images)

The road erases everything. Here in the United States, you can drive for hours in a single cardinal direction without turning the wheel or grazing the brakes. By the time you get to where you’re going, your life story will be rewritten. That, at least, is the dream of the old, worn-out American road story. Joe Westmoreland’s Tramps Like Us isn’t exactly a road story, even though it’s billed that way, with a grainy picture of a two-lane highway adorning the reverse of the title page. The name of the book nods to one of Bruce Springsteen’s most wanderlust-filled songs, but the trips in this novel are merely a backdrop to slower, subtler movements through time. Tramps Like Us is not about quitting small-town suburbia for the metropole so much as it is about how life takes shape through the accretion of minutiae—those small, sensory details and patiently blossoming relationships that crystallize over time into legible experience.

Westmoreland’s debut novel was originally published in April of 2001, 14 years after the author had moved to New York City. It had, to put it mildly, a troubled launch. First, his publisher died a week after the book came out. Then, later in the year, Westmoreland planned a big release party for his birthday, September 11. Needless to say, he had to cancel. “My book was forgotten,” he writes in this edition’s afterword, “even by me.”

Reprinted now after 24 years as an obscure cult favorite, Tramps Like Us takes a long, slow pan across the variegated swirls of gay life in the 1970s and ’80s, from post-hippie sexual awakenings to the era of HIV. “I wrote Tramps Like Us to remember what happened to me and my friends,” Westmoreland says in the afterword, an aspiration whose simplicity matches the plainspokenness of the novel’s style.

In the late 1980s, Westmoreland began writing what he believed would be a memoir with the working title How I Got HIV. As he waded deeper into the retelling, however, he ended up fictionalizing much of the book. His attempts to adhere to memoir left the prose too cluttered with facts to get at any sort of deeper truth, he recalls. So he let the memories bleed together, and the work became a novel (though he and its narrator share a first name). With easy, languid prose, Westmoreland details a coming-of-age story so delicate and diffuse that it barely feels like a narrative at first. It’s only after you’ve gazed into its mists for some time that its larger forms start to appear.

Tramps Like Us winds through a sequence of American locales: Joe flees his suburban hometown in Missouri, moves to Florida, spends a few years in New Orleans, and finally lands in San Francisco with his childhood friend Ali. Almost immediately—by the end of the first page—scenes of formative violence arise. When Joe is 6 years old, his father whips him across the backside in full view of the whole family for wandering out into town on his own. The chronic abuse at the hands of his father leaves enduring marks on Joe as he enters adulthood. “In order not to get too angry and go completely crazy I would retreat into myself and numb out,” Westmoreland writes. Though Joe knows he has no choice but to leave Missouri, he struggles with asserting himself and his desires. He’s both desperate to become someone new and terrified of the transformation it requires.

Though Tramps Like Us is direct and unvarnished, echoing a recognizable strand of queer fiction from the late 20th century—Westmoreland names Dennis Cooper as an influence and is good friends with Eileen Myles, who helped usher the novel to its rebirth—its warmth and gentleness distinguish it from many of its contemporaries. Westmoreland’s writing is never thorny, never concertedly philosophical or self-scrutinizing, never ornamented or filigreed—just wide-eyed, stark, and suffused by turns in fear and wonder.

Current Issue

Blunt sentences slip by with the pleasure of smooth pebbles through a loose hand. The prose is so conversational that it’s sometimes startling, as when scenes of guttural horror read like they’ve bubbled up out of nowhere during a quiet late-night conversation at a local bar. Take, for example, the moment early in the book when Joe reveals that his father has been habitually raping his sisters: “I hated my dad most of the time. I hated him with more than just an adolescent’s hatred of his parents. He treated his kids like we were slaves, using all of us as workhorses. He used my sisters for sex as well. We had to constantly be working around the house or out in our enormous backyard.” Rarely does an “as well” bear quite this much weight.

The quiet Midwestern suburbs that Joe calls home harbor a rot at odds with the family’s public image. Joe’s father is a pillar of his community; everyone says that he must be proud to have such an upstanding dad. Joe does his best to protest the abuse, to no avail: When he picks a fight with his father, his father beats the shit out of him. At night, he lingers at his parents’ open bedroom door, watching his father sleep, wishing that he would leave his sisters alone and take Joe instead: “I don’t think I would have minded it as much as they did.”

Unable to continue living with the horrors inside this seemingly picturesque American family, Joe finally finds the courage to hit the road. In Florida, he has a sexual encounter with a man who he later finds out is rumored to be a murderer. Another man tries to rope him first into hunting snakes, then into making porn. Joe’s still half in the closet at this point, sleeping with men and easily clocked by the drivers who offer him rides, but not out to anyone he cares about—a practicing homosexual with deep reservations about what it would mean to live as a gay man.

On his way out of Miami, Joe stops in New York City, where he meets a photographer named Bud who takes him to Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. There, they stand at the threshold of Joe’s first gay bar. “I didn’t want to go in,” he recalls. “I was afraid if I went in I’d turn queer and I didn’t want to be a big fag with everyone laughing at me.” The twin fears of contamination and humiliation buzz around him. He goes in anyway, and finds a new kind of home.

The tight psychic enclosure of Joe’s origins loosens almost imperceptibly as the novel progresses. Back in Missouri, he comes out to his friend Ali, who’s also queer, and begins his life as an out gay man. Together, Joe and Ali move to New Orleans and partake in the city’s riotous gay nightlife. On New Year’s Eve, high on PCP, Joe finds heaven on the dance floor, “jammed with shoulder-to-shoulder men.” Later, in the bathroom, he melts into a scene of ecstatic group sex. “I wasn’t me anymore,” he says. “I was a thousand different feelings rushing through my body into the guy in front, the guy behind, the whole pulsing crowded toilet.” Sensation overflows its containers, frothing into perfect bliss.

Throughout the book, Ali acts as Joe’s foil, the pugnacious and assertive friend driven by a trenchant desire to make things right. Once they move to San Francisco, Ali begins doing volunteer work, helping refugees from the war in Cambodia after reading a newspaper article about their arrival in the city. If Joe is cool and cautious, Ali runs so hot that he gets them arrested on multiple occasions. Both of them cut striking figures against San Francisco’s gay mainstream: Ali (formerly Frankie) took on his new name after spending time in India, and he dyes his hair deep red with henna. Joe is a dedicated New Waver in a green suede jacket who’s more into Blondie and the Talking Heads than disco. The Castro, for them, is disappointing, well past its prime: “I was expecting to see the kinds of freaks and weirdos that San Francisco is so famous for, but the men looked identical with their tight blue jeans, knit Lacoste alligator shirts, and mustaches,” Joe notes. “The neighborhood was very middle class. It was like a movie set: Main Street, USA, re-created for homosexuals.” There are the suburbs again, winking even from their antithesis.

But a family of freaks does begin to flower around him. Joe and his friends fall into sweet, sensuous routines where the sex and drugs flow freely. They throw parties so rambunctious that the cops pay them three visits in one night. At one party, Joe has an epiphany: that everyone around him has escaped some kind of original torment much like his. “We had all come out of our own separate nightmares to a place where just being ourselves was okay, not dangerous,” he says. “That was a strange new feeling, reason alone to celebrate.”

Tramps Like Us does not nosedive dramatically into its HIV section, which comprises only the last third or so of the book. Instead the virus wafts in, first in the title of a chapter, “How I Got HIV (Version 1, 1981).” The contrast between the chapter’s title and its contents makes for the novel’s only claim to artifice: The title invokes dread, and the story shakes it off. “We had great sex,” Joe recalls of this encounter, which may or may not have been an instance of transmission. “He was very sexy. We were very sexy together.” Later, a chapter subtitled “How I Got HIV: Version 4, Fall 1983” details a scene of ritualized intravenous heroin use among Joe and his friends. He’s no good at pushing in the dose himself; Ali does all the work. “I guess we really are blood brothers now,” muses his friend Felipe. “If one of us gets it then the others will, too.” There’s no menace to this prediction of what might befall friends who share needles, no immediate fear. If it happens, it happens; it’s too far off to worry about. Once they’ve shot up, everyone has group sex together with the apartment’s communal dildo.

Joe hears about people getting sick with what’s first called Gay Cancer, then GRID, then AIDS. The local gay newspaper starts running an obituary column. Then Joe starts seeing his former lovers among the photographs. Next, he gets a dry cough and a spot on his toe; the doctor at the free clinic tells him it’s just a bad cold and a blood blister, and he ends up being fine. There’s a part of him that still believes only the sleaziest of leather queens are succumbing to the plague—the old judgment circling back, viperlike. That’s before more and more of his friends start to seroconvert. They get sick, and Joe cares for them. They march through the streets in silence, carrying burning candles, feeling the weight of a new reality starting to smother the present.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In a pivotal scene late in the novel, Joe is high in bed with Ali, who’s just come out of a harrowing hospital stay. They start kissing, and Joe freezes up: “It was 1986 in San Francisco and to me sex equaled death.” Ali becomes a symbol, a disease vector, an abstraction. But when Joe locks eyes with his friend, he snaps out of it. “As soon as our eyes met he became a person, my friend again and not a sex demon out to ruin my life,” he recalls. “All the worries that were freaking me out slid off my shoulders when I touched him.” They rejoin each other in the sensuous moment, skin to skin, warm and drowsy, connected and sure in their bond.

Tramps Like Us ends before Joe himself receives an HIV diagnosis, letting the “How I Got HIV” chapter titles hang unresolved. Two of his friends urge him to move to Los Angeles, and he decides on the spot to leave San Francisco behind. He hops in a van one more time and speeds away from the city where he found—and lost—his people. Westmoreland also moved to LA in 1986, where he was diagnosed with HIV. The diagnosis prompted him to follow through on a perennial longing to move to New York: “I didn’t want to die in L.A.,” he writes in the novel’s afterword. In New York, he committed himself to writing Tramps, got sick with AIDS for the first time, and ended up responding to treatment when it became available in the mid-’90s. He still lives in New York with his partner, the artist Charles Atlas.

Tramps Like Us is Westmoreland’s only novel, and in the decades since its publication, it remains an electric glimpse into an era marked by stigma and willful misunderstanding. The novel’s greatest achievement is its ability to look into a time when illness and institutional abandonment foreclosed living possibility—and to enliven it from the inside. Tramps Like Us counters the petrified narrative that HIV passes from body to body in moments of carelessness or cruelty. Just as easily, it can move through true familial love. Westmoreland asks you to look his characters in the eye, to feel their essential humanness as they love each other while their world first blooms and then falls apart.

Don’t let JD Vance silence our independent journalism

On September 15, Vice President JD Vance attacked The Nation while hosting The Charlie Kirk Show.

In a clip seen millions of times, Vance singled out The Nation in a dog whistle to his far-right followers. Predictably, a torrent of abuse followed.

Throughout our 160 years of publishing fierce, independent journalism, we’ve operated with the belief that dissent is the highest form of patriotism. We’ve been criticized by both Democratic and Republican officeholders—and we’re pleased that the White House is reading The Nation. As long as Vance is free to criticize us and we are free to criticize him, the American experiment will continue as it should.

To correct the record on Vance’s false claims about the source of our funding: The Nation is proudly reader-supported by progressives like you who support independent journalism and won’t be intimidated by those in power.

Vance and Trump administration officials also laid out their plans for widespread repression against progressive groups. Instead of calling for national healing, the administration is using Kirk’s death as pretext for a concerted attack on Trump’s enemies on the left.

Now we know The Nation is front and center on their minds.

Your support today will make our critical work possible in the months and years ahead. If you believe in the First Amendment right to maintain a free and independent press, please donate today.

With gratitude,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

Former Disney CEO Michael Eisner berated the company’s capitulation before authoritarian MAGA threats, but in many ways, he set the example.

Ben Schwartz

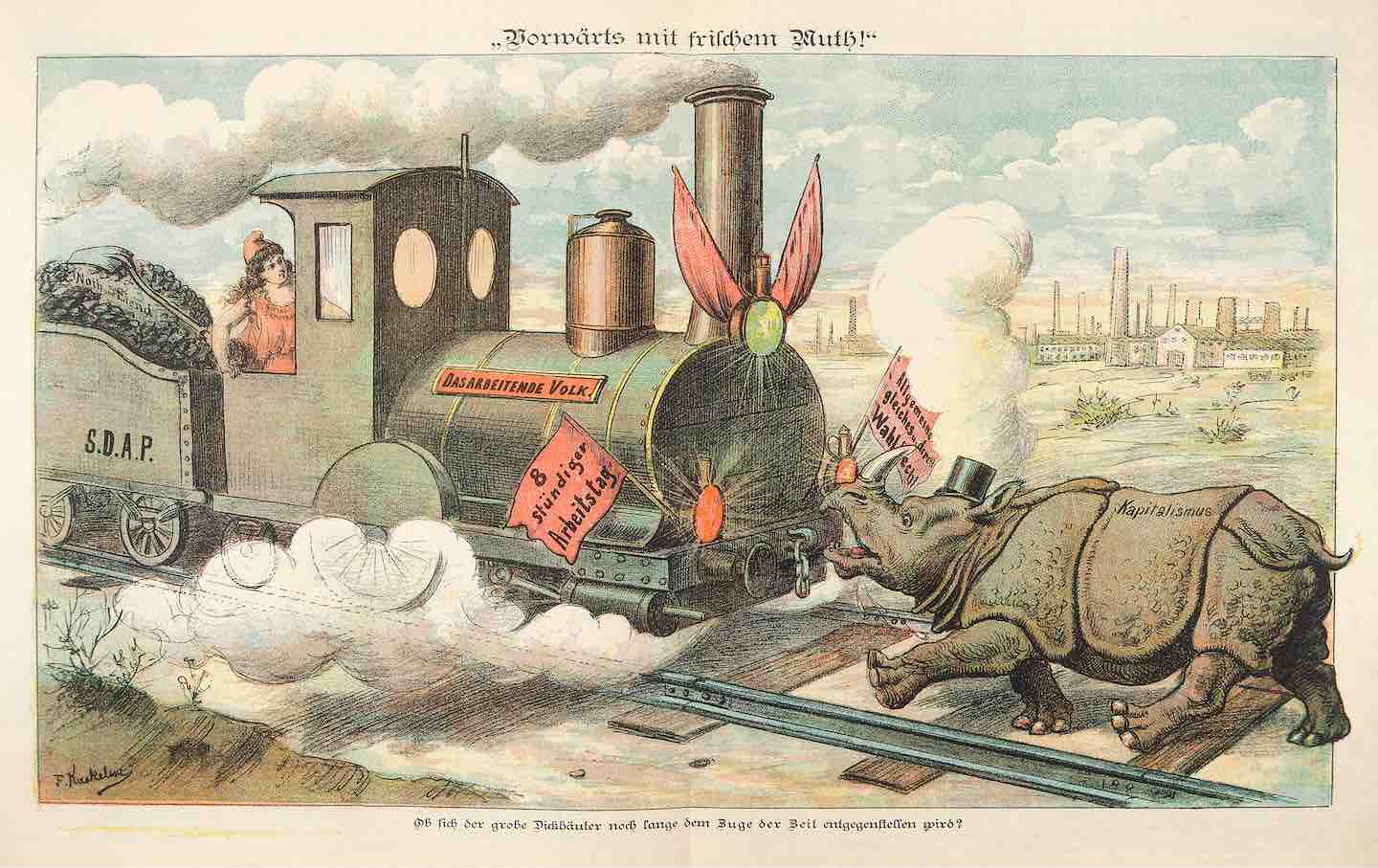

According to John Cassidy’s century-spanning history “Capitalism and Its Critics”, the system lives on because of its antagonists.

Books & the Arts

/

Erik Baker

A conversation with Thea Riofrancos about her new book “Extraction” and the hidden cost and obscured history of the capitalist push to monetize the energy transition.

Books & the Arts

/

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

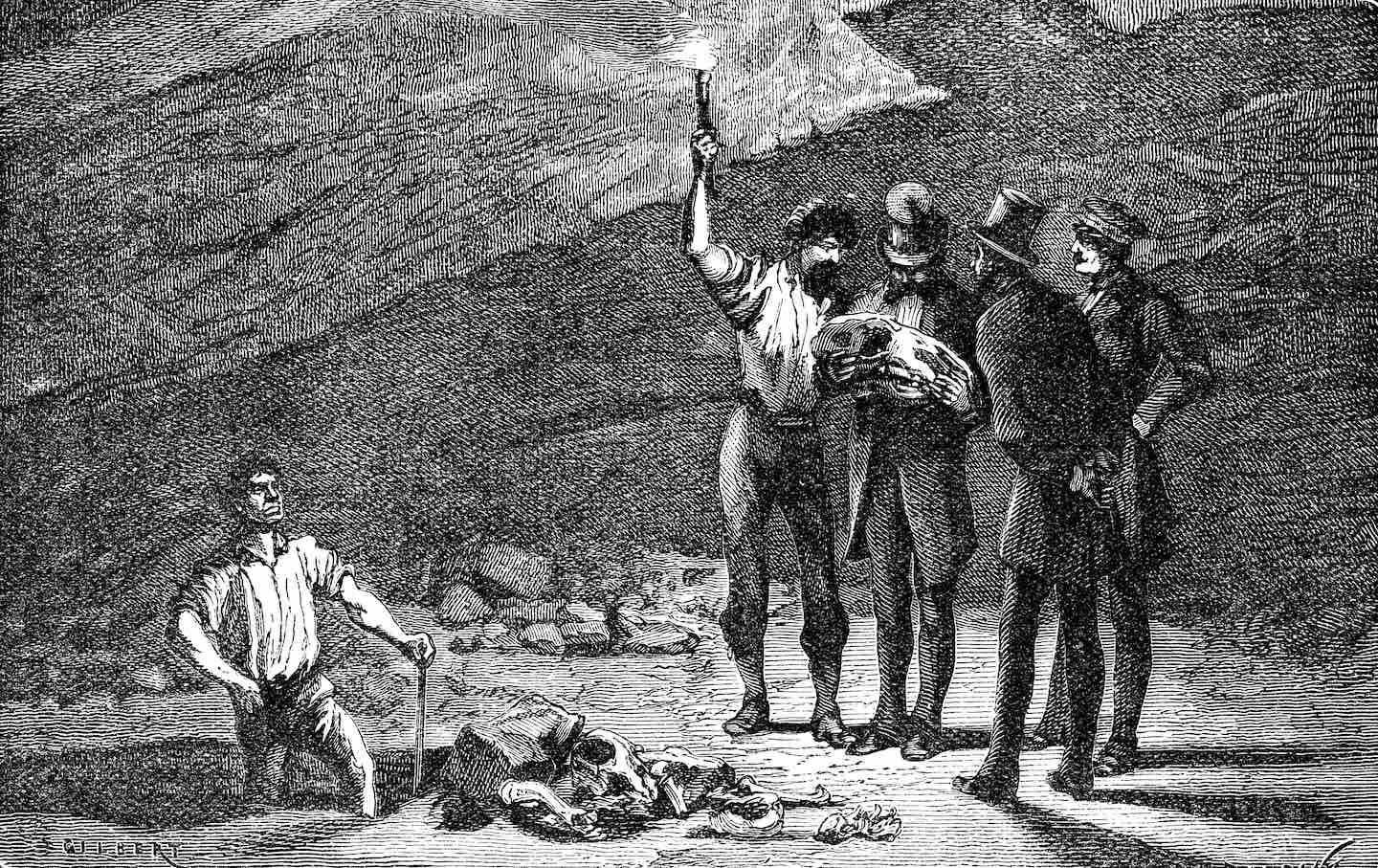

When the remains of prehistoric creatures were discovered in Europe and the United States, it opened up a vociferous debate on the nature of time and the purpose of science.

Books & the Arts

/

Andrew Katzenstein

Karen Hao’s recent book on the company argues that its ambitions are not merely about scale or the market but the creation of a global force that rivals a colonial power of old.

Books & the Arts

/

Andrew Deck