Make art with pythons and lionfish

Explore

SSome of nature’s most destructive forces are beautiful to behold: a lionfish that drifts like a fan of jewels in the water, a python that glides with muscular grace through the grass, a carp that glows silver as it leaps from a river.

These creatures can destroy entire ecosystems.

They are invasive species. Transported across oceans by global trade, released by human negligence or deliberately introduced for industry, they multiply in habitats that are unprepared for their welcome. Then they devour resources and displace existing animals. Studies show that lionfish can reduce populations of native reef fish by up to 80% in just a few weeks. Burmese pythons in Florida are responsible for the decimation of more than 90% of the populations of certain small mammals. Carp invade waterways so densely that boats have difficulty passing. These losses reverberate outwards: food networks collapse, ecosystems suffocate. By conservative estimates, invasive species now cost the global economy hundreds of billions of dollars annually and contribute to more than half of all documented extinctions.

“Beauty is edged with menace.”

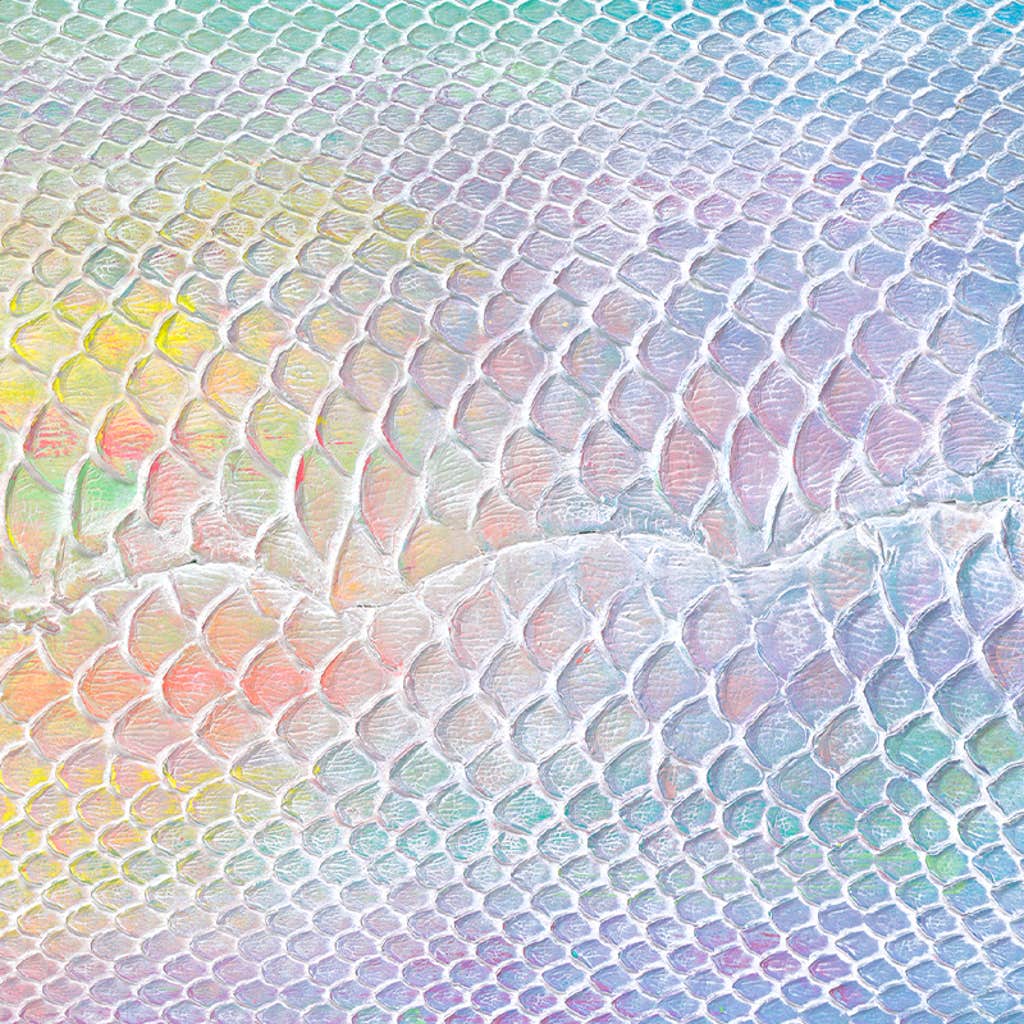

But one artist is turning these animals into works of art to make the dangers more visible. Laura Shape takes the skins of invasive species, which are usually discarded after being trapped or hunted, and uses them as raw material for shimmering textured paints. Shape works with a group called INVERSA, which turns hides into leather and other soft materials like fabric and decorative panels. Several Shape pieces are currently presented in Under the seaa virtual show supported by UNESCO. She also aims to place her works in public spaces, such as hotels, airports and hospitals, in regions affected by ecological disruption, so that art lives where the problem is most urgent.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or register now.

“The material is the message,” explains Shape. She makes lionfish skins shine like stained glass and weaves python skins into sculptures that ripple like rivers. “When I use invasive fish skin or python leather, I’m imposing the ecosystem into the artwork. You can’t separate them.” His point is not metaphorical but ecological. These materials are literally parts of the problem, transformed into shapes that require attention.

And attention matters. Research in conservation psychology shows that emotional connection and beauty can inspire environmental action more effectively than data alone. A painting made of lionfish leather catches the eye, but it also carries the memory of a predator that empties the reefs. A sculpture sewn from carp skins may seem meditative, like flowing water, until the viewer remembers how carp choke rivers. Shape tells me, “I want people to feel both fear and discomfort. That’s what makes it real.”

Science still offers the primary means of controlling invasive species: monitoring, removal, prevention, and habitat restoration. Yet art can play a role that science alone cannot. This creates intimacy. It brings the crisis into salons and galleries, into the hands of collectors who now hold a fragmentation of the ecological imbalance.

Some critics retort that aestheticizing the invaders risks glorifying them. But the best of this art resists this trap. This highlights the paradox rather than erasing it. The objects are beautiful, but the beauty is tinged with menace. They are a reminder of what happens when ecosystems lose balance and what humans can do, however imperfectly, to repair them. “Every invasive species tells two stories,” Shape explains. “The story of collapse and the story of resilience. My job is to bring those pieces together, to make people look at each other and then care.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or register now.

Invasive species test the resilience of the natural world and human imagination. They reveal how fragile the ecological balance is, how quickly beauty can tip towards destruction. But they also remind us that what is broken can be reinvented. When an invader’s body becomes a painting or sculpture, it is not simply a decoration. It is an invitation to see differently: to confront the damage we have caused and to imagine the repair woven from its very fibers.

More than Nautilus on invasive species:

“The strange odyssey of the starlings“ The Legacy of America’s Most Hated Bird

“I heard the bray of the wild donkey» On the trail of a new understanding of invasive species

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or register now.

Enjoy Nautilus? Subscribe for free to our newsletter.

Main image: Laura Shape