Immigrants make up more than 30 percent of Nobel science prize winners since 2000

October 14, 2025

5 min reading

Immigration has shaped the lives and careers of 30% of recent Nobel Prize-winning scientists

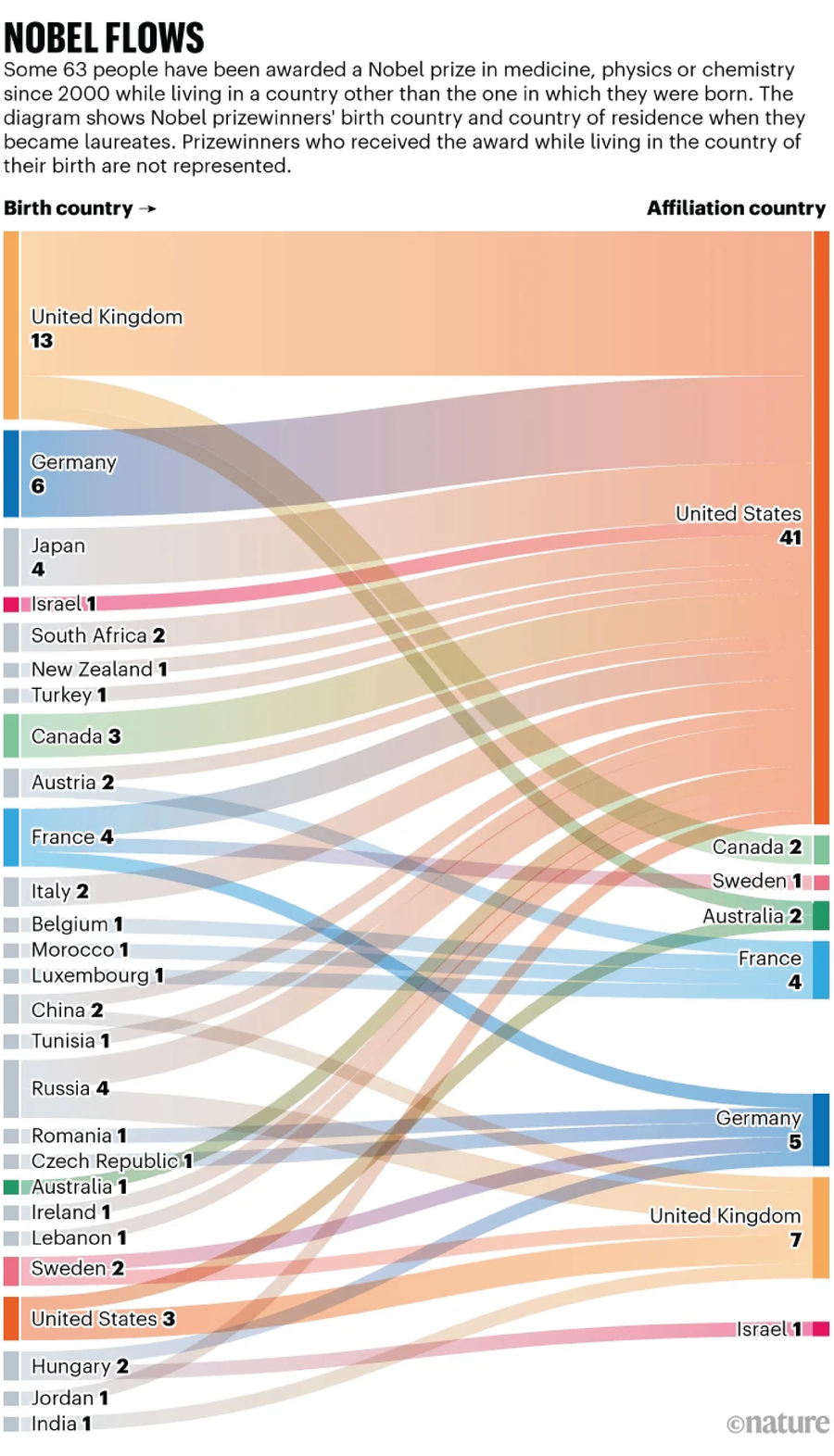

Of the 202 Nobel Prize winners in physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine this century, less than 70% are from the country in which they received their prize. These graphs trace their journeys

Omar Yaghi with molecular models of some of his porous structures, called metal-organic structures or MOFs. COFs have similar internal structures, but are held together by strong covalent bonds rather than metal atoms.

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

Of the 202 Nobel Prize winners in physics, chemistry and medicine this century, less than 70% are from the country in which they received their prize. The remaining 63 laureates left their countries of birth before winning a Nobel Prize, sometimes crossing international borders more than once, a Nature » shows the analysis (see “Nobel Flow”).

Nobel laureates who have emigrated to other countries include two of the three chemistry winners announced Wednesday. Richard Robson was born in the United Kingdom but now lives in Australia. And Omar Yaghi, who now resides in the United States, became the first Nobel laureate in science of Jordanian origin. Two of the three physics winners for 2025 are also immigrants: Michel Devoret was born in France and John Clarke in the United Kingdom, but both reside in the United States.

Nature; Source: Nobelprize.org

On supporting science journalism

If you enjoy this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscription. By purchasing a subscription, you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Immigrants have long played an important role on the Nobel stage, including illustrious scientists such as Albert Einstein, who left his native Germany for Switzerland (and later the United States), and Marie Curie, who left her native Poland to work in France. Indeed, the most fruitful scientific opportunities – the best training, equipment and research communities – are dispersed across the world. “Talent can be born anywhere, but opportunity isn’t,” says Ina Ganguli, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “I think that’s why we see so many foreign Nobel laureates.”

The new analysis comes as the international flow of scientists and students faces growing obstacles. In the United States, for example, widespread subsidy cuts and stricter immigration policies implemented this year by President Donald Trump’s administration threaten to lead to a “brain drain.” Such restrictions “will slow the pace of very innovative research, period,” says Caroline Wagner, a science and technology policy specialist at The Ohio State University in Columbus. The White House did not respond to a request for comment on the effects of Trump’s policies.

At the same time, Australia has capped the number of international students its institutions can enroll each year, and Japan has proposed reducing financial support for graduate students from other countries.

Common destination

Among those who have already crossed borders is Andre Geim, a physicist at the University of Manchester, UK, and 2010 physics laureate. Born in Russia to German parents, Geim says he has “bounced around like a pinball” throughout his research career, holding positions in Russia, Denmark, the UK and the Netherlands. “If you stay there your whole life, you miss half the game,” he says.

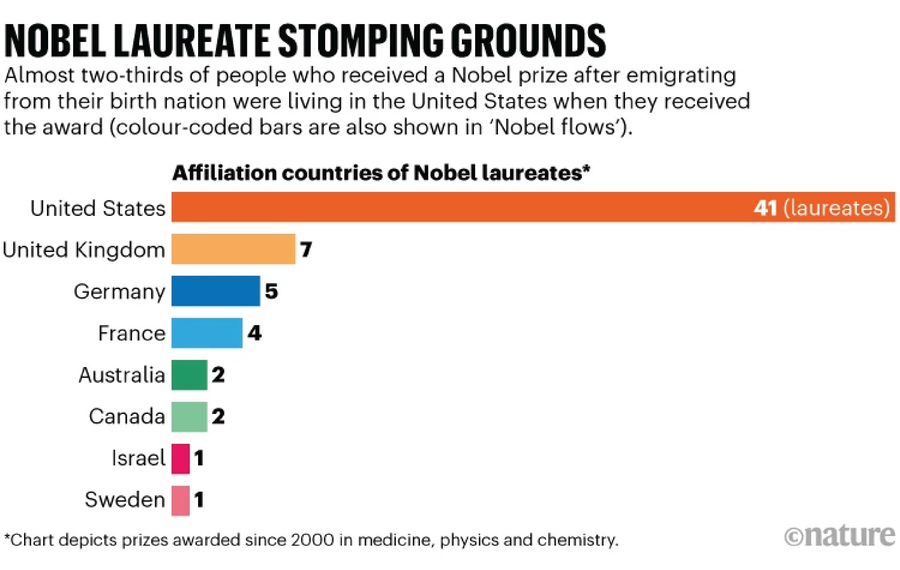

Of the 63 laureates who won the prize after leaving their home countries, 41 lived in the United States at the time of their Nobel award. After World War II, the United States became a global hub of science, Ganguli says. International researchers flocked there for its generous grants and top-tier universities (see “The stomping ground of Nobel laureates”). “What we have in the United States is unique. It’s a destination for the best students and scientists,” says Ganguli. The second most popular landing spot was the United Kingdom, home to seven of the Nobel laureates who had emigrated by the time they received the fateful phone call from Stockholm.

Nature; Source: Nobelprize.org

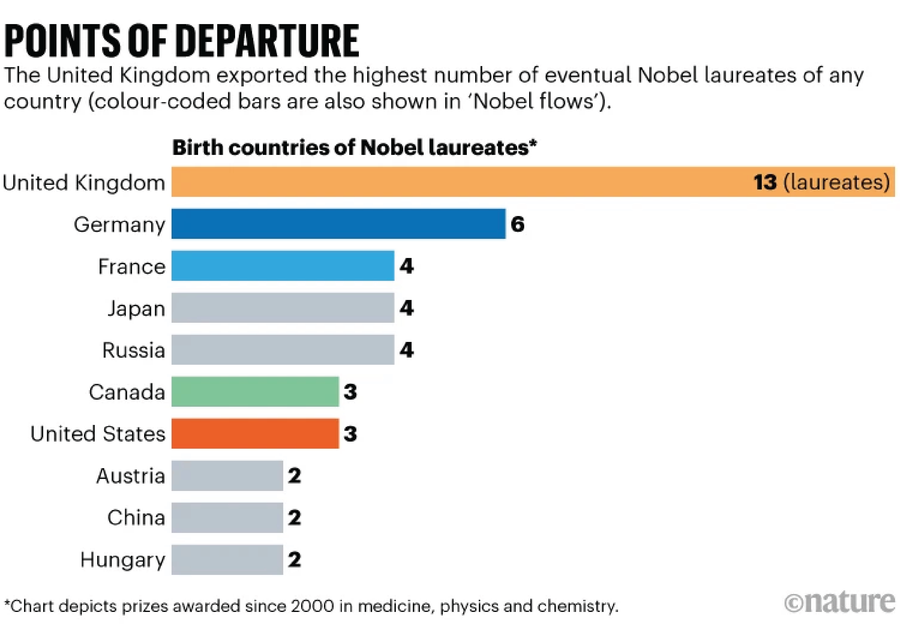

But the United Kingdom has also seen future winners leave. Thirteen Nobel Prize winners born there won the prize while living elsewhere (see “Starting Points”), perhaps attracted by higher salaries and more prestigious positions, Wagner says. A significant number of future Nobel laureates also left Germany, with six expatriate laureates, as well as Japan, France and Russia, each with four expatriate laureates.

Nature; Source: Nobelprize.org

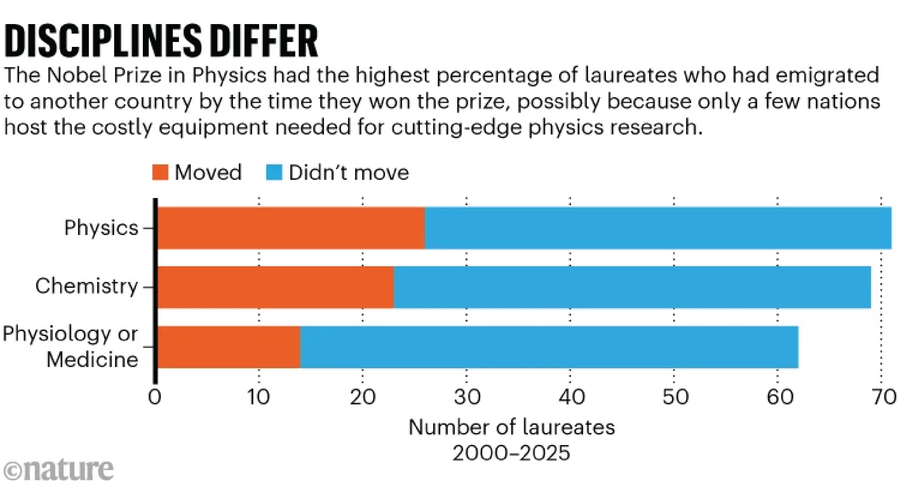

Among the Nobel Prize science categories, physics has the highest proportion of foreign-born laureates so far this century: 37% (see “Disciplines differ”). Just behind, we find chemistry with 33%, and finally medicine with 23%. According to Wagner, physics probably comes out on top because of the cumbersome nature of its equipment. The expensive colliders, reactors, lasers, detectors and telescopes needed for world-class physics research are found mainly in a few world-class countries. “So the best researchers will probably go to places with the best equipment. Medicine is not a field that requires a lot of equipment, so it’s easier to stay at home,” says Wagner.

Nature; Source: Nobelprize.org

Move on

The future of the interaction between immigration and the Nobel Prizes is unclear. Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom have all adopted restrictions that have reduced the number of international university students. The Trump administration has slashed billions of dollars in scientific research grants so far this year. And a new U.S. policy mandates $100,000 per H-1B visa application, which some foreign-born researchers rely on to work in the United States.

Already, international researchers are considering leaving the United States, while other countries are ready to woo them. France, South Korea and Canada have established programs to attract American researchers with prizes and scholarships, for example. The European Research Council, which funds research in the European Union, is offering up to 2 million euros ($2.3 million) to scientists who relocate their laboratories to the EU, in a bid to help those leaving the United States.

The result, Ganguli says, could be a mass exodus similar to the flood of scientists who fled Germany after World War II and Russia after the Soviet Union officially dissolved in 1991. “There’s a big loss of human capital and people will go to another country,” Ganguli says, although she still doesn’t know exactly what that other country might be. Although countries like Belgium and France are taking steps to attract American scientists, their salaries are probably not high enough to convince many researchers to jump ship, she adds.

Wagner agrees that it is impossible to know where the next Nobel center might be, in large part because of the array of political, economic and social factors that contribute to fostering a just research environment. “Smart people disperse. But will they recreate that kind of magic? That’s an open question,” Wagner says. It is also difficult to predict when current political changes might result in a notable change in the list of winners. Scientists win Nobel Prizes at all stages of their careers, and researchers are probably already working on the next set of discoveries that will merit Nobel Prizes. The effects of the scientific revolution will probably only be fully felt in the “very long term”, Wagner believes. For now, Geim urges nations not to close their borders to new talent. “Mobility benefits everyone. Each newcomer brings new ideas, new techniques and different ways of approaching old problems,” he says. “Countries that welcome this mix remain vigilant. »

With additional reporting from Nicky Phillips and Alexandra Witze.

This article is reproduced with permission and has been published for the first time October 10, 2025.