The problem of stacking mathematics blocks has an absurd solution

This mathematical problem of block stacking has an absurd solution that you must see to believe

In principle, this impossible mathematics allows a bridge without glue of stacked blocks which can stretch through the large canyon and endlessly

Here is a breathtaking experience that you can try at home: Gather children’s blocks and place them on a table. Take a pâté of houses and push it slowly on the edge of the table, inch by inch, until it is on the edge of the fall. If you have patience and a regular hand, you should be able to balance it so that exactly half is suspended. Push it further, and gravity wins. Now take two blocks and start again. Stack on each other, how far can you get the end of the upper block to prick the edge of the table?

Continue. Stack as many blocks as possible, what is the most distant overhang you can achieve before the whole structure is overthrown? Is it possible that the tower extends a complete block length beyond the table lip? Does physics authorize two block lengths? The amazing answer is that the stacked bridge can stretch forever. In principle, an independent block stack can extend over the Grand Canyon, no required glue.

On the support of scientific journalism

If you appreciate this article, plan to support our award -winning journalism by subscription. By buying a subscription, you help to ensure the future of striking stories about discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

Do not click on “Discover” on an infinite pack of JENGA blocks. Real practices such as forms of irregular blocks, air currents and the overwhelming weight of an endless building can hinder your engineering aspirations. However, understanding why overhang has no limits in an ideal mathematical world is enlightening. The explanation depends on the harmonic series of mathematics and the physical concept of the center of mass, on two apparently simple ideas with excessive power. [For more fun, check out: How Tall Can You Build a Tower without It Toppling?]

Your intuition could tell you that a single block can hang half of its mass beyond the edge of the table before switching. But why is it like that? Each object has a center of mass – a unique point to which we can imagine that the weight of the object is concentrated when we think of balance. As long as the center of mass is above the table, the object remains in place. However, when the center of mass passes on an edge, gravity will pull everything. In the case of a spoon, an element with an irregular weight distribution, we can hang more than half of the utensil handle on an edge before it will switch because the center of mass is closer to its head, where more weight resides. For our stacked bridge, we assume that our blocks are all identical, with a uniform density (that is to say that they are not more dense in certain parts than others), so that each of the mass is in the middle.

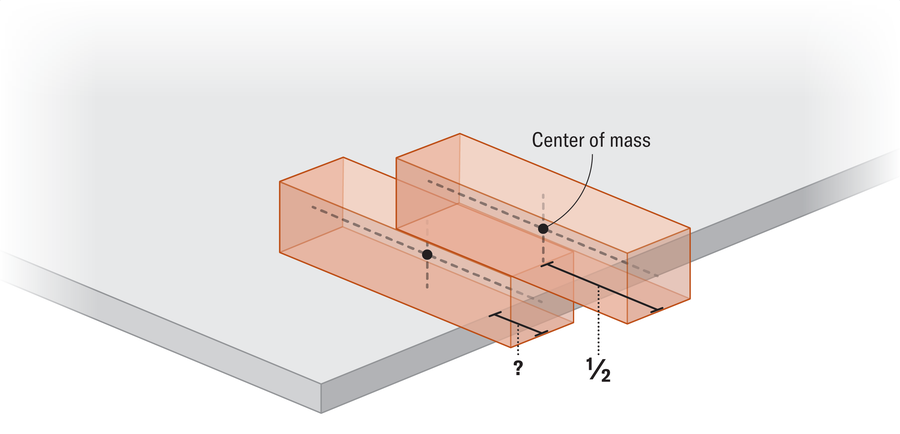

When we add more blocks, we must take into account the center of mass throughout the tower. Consider the case of two blocks. We know that the upper block can extend half of its mass beyond the one below. But after doing this, how far can we push the lower block?

For more simplicity, let’s say that each block has a length of 1 and a mass of 1. You will find that the lower block can only come out a quarter of the path (compared to half its length on the edge when it was alone). At this stage, the mass center of the upper block and the mass center of the lower block are equidistant on the edge of the table (the center of mass of the upper block is a quarter to the right of the edge, and the mass center of the lower block is a quarter to the left of the edge). So the combined Center of Mass of two -block system Building perfectly balanced above the edge of the table.

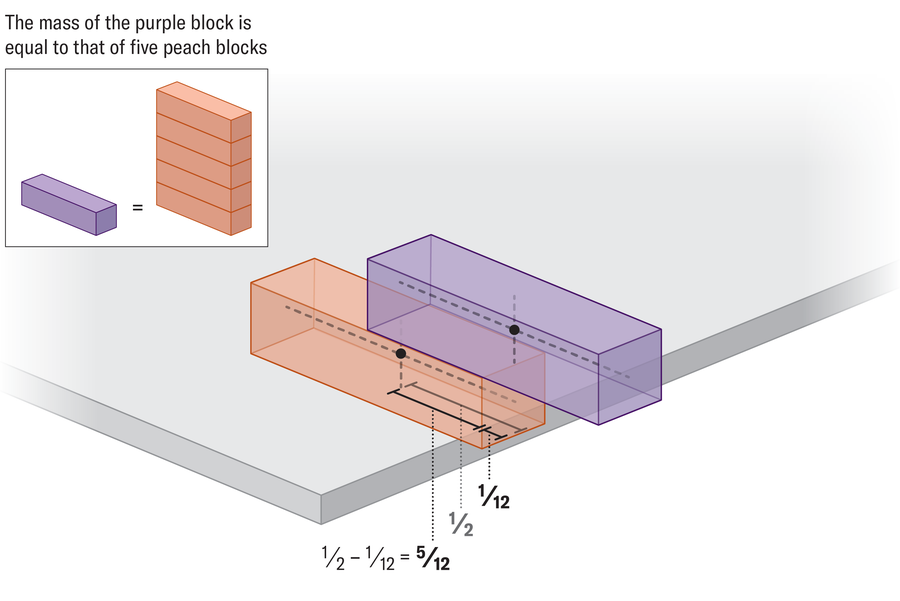

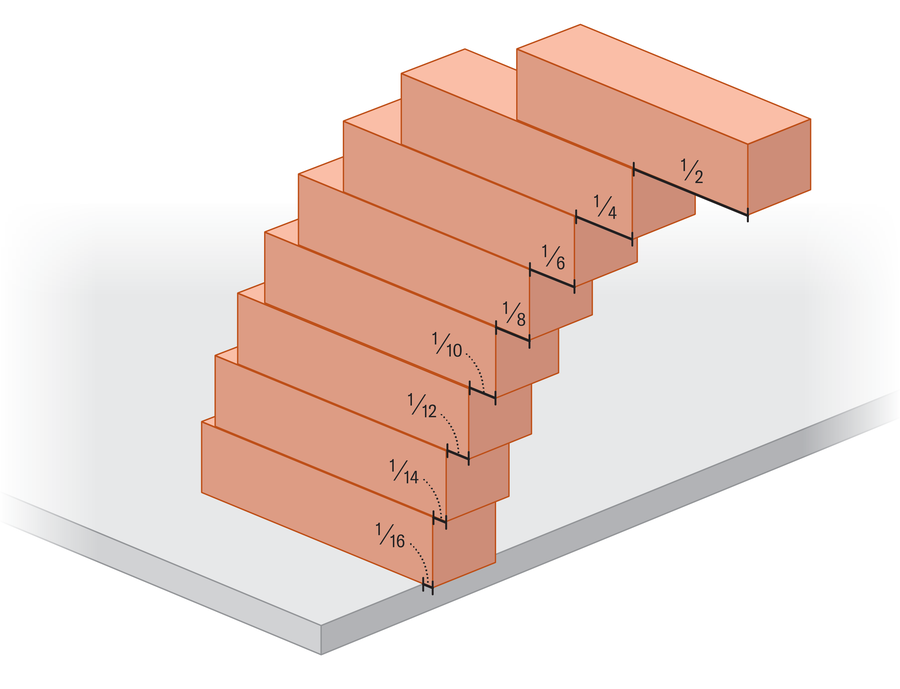

A model emerges while we continue to add blocks to the structure. The upper block extends 1⁄2 Beyond the one below, the second block extends 1⁄4 Beyond the block below, the third extends 1⁄6The fourth extends 1⁄8The following blocks extend 1⁄10,, 1⁄12and so on. To see why, let’s look at another example. Suppose we have a stable tower that contains five blocks, and that we want to add a sixth block below, then slide the entire structure as far as possible. It is useful to conceptualize this image as only two blocks: one with a mass of 5 at the top of a single block with a mass of 1. We will first advance the heavy block as far as it will go so that its center of mass is just above the edge of the lower block. We can then push the lower block exactly 1⁄12 of a unit beyond the edge of the table. How do we know that?

Again, the answer comes down to balance the mass centers of the two blocks, only this time, because the lower block is five times lighter, its center of mass must be found five times further on the top of the table to counter the weight of the heavier block. This is known as the law of the lever – think of how a book feels heavier in your palm, the more you distance it from your body, so a pocket book in an entirely extensive arm may seem equivalent to a manual held near your chest. The distance between the center of mass of the upper block and the edge of the table is 1⁄12and the distance for the lower block is 1⁄2 – 1⁄12 = 5⁄12or five times more. A similar calculation reveals the correct overhang at all levels of the tower.

Answer our opening question (how far can the tower extend?) Contrary to the addition of all these successive overhangs. If you have 10 blocks, they can extend to 1⁄2 + 1⁄4 + 1⁄6 + 1⁄8 + 1⁄10 + 1⁄12 + 1⁄14 + 1⁄16 + 1⁄18 + 1⁄20This represents approximately 1.464 block length beyond the edge. But what is the limit to how far we can stack the blocks? To do this, we must infinitely add several of these narrowed terms. The resulting model resembles a striking resemblance to one of the most famous sums in mathematics, the harmonic series, which takes the reciprocal of each number of counts (that is to say 1 divided by each positive integer) and summarizes them all:

1 + 1⁄2 + 1⁄3 + 1⁄4 + 1⁄5 + …, and so on forever.

If you look carefully, you may notice that the overhangs of the block stacking problem are exactly half of these terms: 1⁄2 + 1⁄4 + 1⁄6 + 1⁄8 + 1⁄10 + …

The calculation, the branch of mathematics which digs in the way things change, teaches us that even when it addes infinitely many narrowed terms, the sum converges on a finite value and sometimes it diverges endlessly. The total of the harmonic series develops incredibly slowly. The first 100,000 mandates represent approximately 12.1 while the first million terms are only about 14.4. However, at an implacable snail rate, the harmonic series develops forever.

Each individual overhang in the block stacking problem is half a term in the harmonic series. Because half of the infinity is still endless, the potential overhang of the tower also has no link.

Of course, translating pure mathematics into practice is always accompanied by obstacles, but the problem of blocking blocks offers a challenge for fun dexterity. With only four blocks, you should be able to extend the top of the length of the complete block beyond the edge (1⁄2 + 1⁄4 + 1⁄6 + 1⁄8 = ~ 1.042). To make my diligence due to journalistic, I tried this at home with playing cards on my coffee table. After a few minutes of DIY of the patients, I managed to balance the upper map just beyond the edge, with it suspended entirely from the table, and I felt like a magician.

Two complete block lengths beyond any surface would require 31 rooms. Meanwhile, 100 million pieces would not even give you a complete length of overhang of 10 blocks because the sum of the first 100 million terms of the harmonic series all divided by 2 is equal to around 9.5. It will therefore take grain to expand on the Grand Canyon. On a huge scale, physics comes into play to reverse the pleasure of mathematicians. But under idealized conditions where the center of mass and the harmonic series alone govern the perch, the possibilities are literally endless.