Reading the body of Gustav Eckstein has a head

Explore

I I want to tell you about the most absolutely wild book I have never read on the human body and mind. I discovered it from the disabled reference of an author in New York Times book review And bought it in an online antique bookstore.

But I don’t know where to start because if scientific writing is a round hole, this book is a giant square ankle. The best I can say is The body has a head by the doctor and teacher Gustav Eckstein, published in 1969, reads as Grey’s Anatomy Written by James Joyce.

The descriptions of the biological mechanisms begin quite directly, explaining, for example, the stomach is in the form of J. But the descriptions soon take off on the metaphorical reveries which compare what is happening inside our body to the carnival of life outside of them. Talk about interconnection. Of science bridging art. Let’s have some examples.

• While the attacking molecules and the food molecules engage in a chemical fight, the muscles of the stomach wall act on the softening lunch. Harassment. A maceration. A crushing. A push forward. A constant pressing on the late cute net or goose like pressing on a tube of toothpaste. Nothing that enters the digestive tract once is authorized to stroll.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus members benefit from experience without advertising. Connect or join now.

• Why do we have pain? Why do we have this sense forever to wait? Someone, too discriminating, called that music. Painful. The whole orchestra, all violins in particular, first, second, viola, cello, bass, from time to time a complaint of the oboe, a brass accident, a rumble of the drums. For what? The creature must be warned. The pain prevents destruction from going too far by making a quick announcement whenever something has started to threaten the flesh, and something is almost always.

• A roadmap is in the minds of each neurologist or neurosurgeon. He sees the events. The urine enters the reservoir, rises in the reservoir, a report returns to the owner, who makes a decision, telegraph the first orders from the spirit to the brain, which releases the center of the spine from its duty to stick the tide, and the wall of the bladder and its double valve output enter into action. The bladder contracts, the internal exit valve is released, the urine continues to press, the external relaxes, the valves open and everything is fine. The assistance is provided by the abdomen, whose muscles hold firmly while everything below is relaxing. “A machine made by the hand of God.” Relaxing could have been changed by passing if the gentleman had, for example, decided to finish his crossword puzzle.

Believe me, these are just some of the lighting rockets of this exhibition volcano. 784 pages! A reviser in the Journal of the American Medical Association In 1970, the book “was told in what I call a floating, unruly and endless hyperbolic style, a kind of flamboyant free association.” As if it was a bad thing!

You don’t read the first page book to last. The chapters are short with many subsections, so you can sneak anywhere. Along his serpentine paths, you will meet Hippocrates, Descartes, Shakespeare, Thomas de Quincey, Beethoven, Louis Pasteur, Einstein, Pavlov, Poe, Nietzsche, Phineas Gage, and a distribution of surgeries from their 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, described through their tales.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus members benefit from experience without advertising. Connect or join now.

Of course, there is a big hole here. A fault in the stars of Eckstein. Women in philosophy, science, medicine and art are seriously absent from his opus. (Georgia O’Keeffe deserves a few lines to illustrate the subjective perception caused by the interaction of eye angles and neurons of vision.) The body has a head is also autobiographical, I suspect, because anatomy lessons are often expanded by scenes from a hospital, where Eckstein coldly comments on all kinds of macabre scenes, chatting like a rascal on other doctors, nurses and patients.

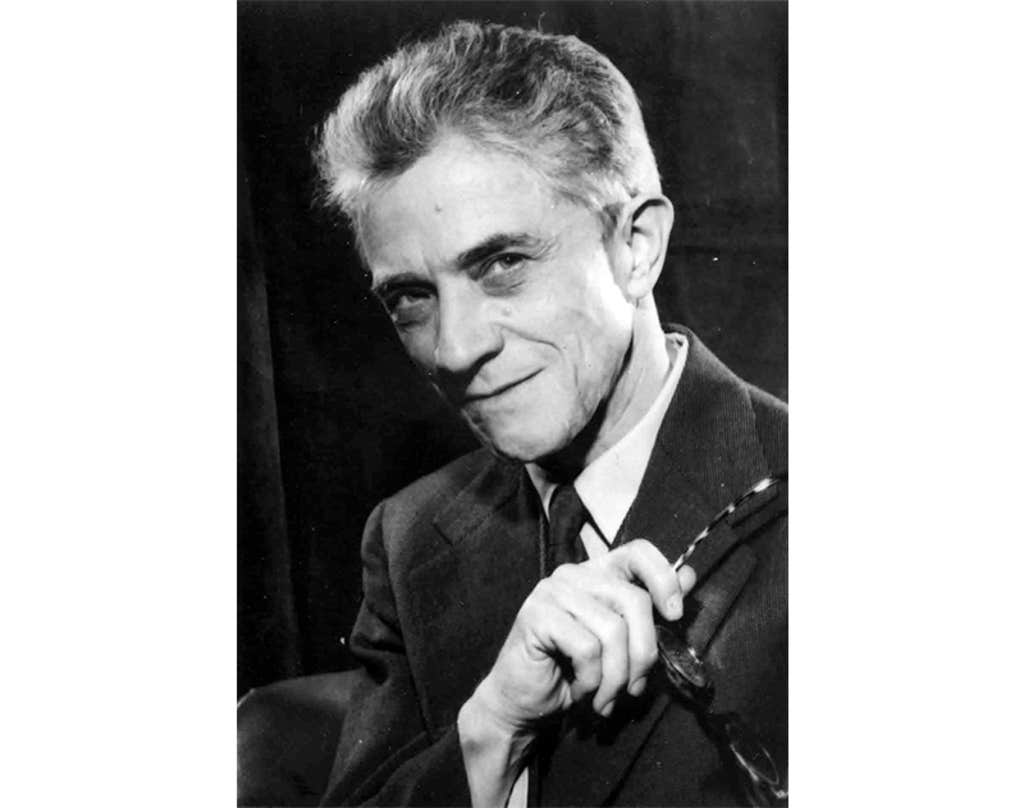

Who was Gustav Eckstein? He was a dentist from 1911 to 1918, then obtained an MD, then settled in the long term as a professor of physiology at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Cincinnati. He lived nearby in a resident hotel for 40 years. He was briefly married when he was young. He died at 90 in 1981. His friends, students and patients knew him like Dr. Gus.

“Dr. Gus was a light man with an unruly hair shock at the top of a too large head,” wrote his friend and colleague doctor, the late Stanley Block. “He was curious about everything. And everything aroused his curiosity.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus members benefit from experience without advertising. Connect or join now.

Before The body has a headEckstein had written eight pounds and a room, on an Irish woman in America troubled by her varied father; He failed on Broadway. One of the books concerned the Canaries and another, Everyday miracleAbout the animals around him, notably Willy Le Cat, who every Monday evening at 7.45 am crossed the city to sit in a window and watch a bingo match. How did Eckstein know? He followed it. Eckstein loved his pet Macaw and on Saturday evening took him to the Symphony, hidden under his coat.

Eckstein installed a wallpaper inside its university laboratory door. It was to make sure that the flock of Canaries flying freely in his laboratory did not come out. Nor the mice that made the laboratory board their playground. Visitors who have passed and dodged birds and mice would invariably find Eckstein to his typewriter, peck, carrying a straw hat to keep the bird of bird – nomable on counters, books and chairs – about her hair.

I can’t imagine a more perfect scene to capture the author behind The body has a head. He was there, by typing in a fury, canaries above, mice below, smiling with biting joy, pouring everything with his brain and his brain, making literature like no other science and medicine.

Image of lead: Lynea / Shutterstock

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus members benefit from experience without advertising. Connect or join now.