Cartography of the displacement of the Kamchatka earthquake

The surface of the earth may seem stable and immutable, but it is anything but static. The tectonic plates that make up the rigid exterior layer of the planet are like puzzle pieces that crowd and climb against each other – often slowly but sometimes in violent and chilling tremors that we know in the form of earthquakes.

After an earthquake, seismometers are among the first tools that scientists take care of information. The global networks of these ground sensors measure vibrations in the earth’s crust and the upper mantle and are used to identify the location of the epicenter and the intensity of the tremors. However, seismic networks have limits. In some cases, they cannot measure the extent of a break with great precision, in particular in the fields where local seismic networks are rare.

A new remote sensing technique called interferometric synthetic opening radar (Insar) helps to fill these shortcomings. In August 2025, for example, the technique measured the movement of the soil, as well as signs of imminent volcanic activity, after a major earthquake shaken the Kamchatka peninsula in eastern Russia.

Insar provides travel measures – the ground offset far or to the satellite – across hundreds of square kilometers. Developed for the first time in the 1980s, the method allows scientists to map the breaks of earthquakes with impossible precision from seismic networks alone by comparing two or more images Sar taken before and after an earthquake.

The above map shows the quantity of movement of the soil caused by a powerful earthquake which struck off the peninsula on July 29, 2025. The red zones were pushed mainly towards the east by the event of magnitude 8.8, one of the strongest recorded by the modern seismic instruments. The dotted lines highlight the defects of the keys and the limits of the plate in the region. Small white spots in the southern part of the peninsula are areas where the trip could not be measured.

The power of the Insar

Based on the data of previous earthquakes, scientists knew the location and basic geometry of the Grande Faille, a “megathrust”, east of the peninsula, where the Pacific dense plate slides under the Okhotsk plate from the Kuril – Kamchatka trench. But the Insar cartography helped researchers identify the parts of the flaw moved during the earthquake and to what extent, Eric Fielding, a geophysicist in Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), explained.

“Note how much trips there were near the epicenter and how the greatest trips were in the southwest more than 200 kilometers, near the southern tip of the Kamchatka peninsula,” he said. The technique has measured an east movement of the southernmost part of the peninsula of more than 1 meter (3 feet), as well as a slight movement down in the earth’s surface.

This type of information has practical uses and, in some cases, rescue. In conjunction with satellite data of seismic and global navigation, scientists of the American geological survey use ISAR data in models which define exactly where and by how many defects slips, the information used in the tsunami forecasting models. Moving mapping can also be useful the day after an earthquake by quickly identifying the most affected areas and facilitating emergency intervention to decide how to deploy limited resources. In this case, damage to the infrastructure of the peninsula were minimal despite the intensity of the earthquake because the epicenter was offshore, the largest shift in the southern tip, and the peninsula was so little populated, Fielding said.

The power of the ISAR is that it increases other observations to provide a more detailed understanding of a default, noted Andrea Donellan, head of the land department of the Purdue University, atmospheric and planetary sciences and a distinguished guest scientist. “This can be used to study how the flaw slips after the earthquake, both quietly and via replicas.” These ideas shed light on future assessments of the risks of earthquake and improve understanding of how defects behave on a global scale, she added.

The card at the top of the page is based on the data of the advanced imaging and rapid analysis team (ARIA) of JPL, which develops cutting -edge deformation measures, change detection methods and physical models to be used in science and risk response. The team used the PALSAR-2 sensor SAR data on ALOS-2 from the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (Advanced Land Observing Satellite-2) for the Insar analysis in order to measure the quantity that the soil has evolved in relation to the satellite.

The technique detects both the horizontal and vertical movement, although in this case, most of the displacement was horizontal. The ALS-2 data were acquired on August 2, 2025, four days after the earthquake. For comparison, the researchers used a basic radar image captured by the sensor on September 13, 2023.

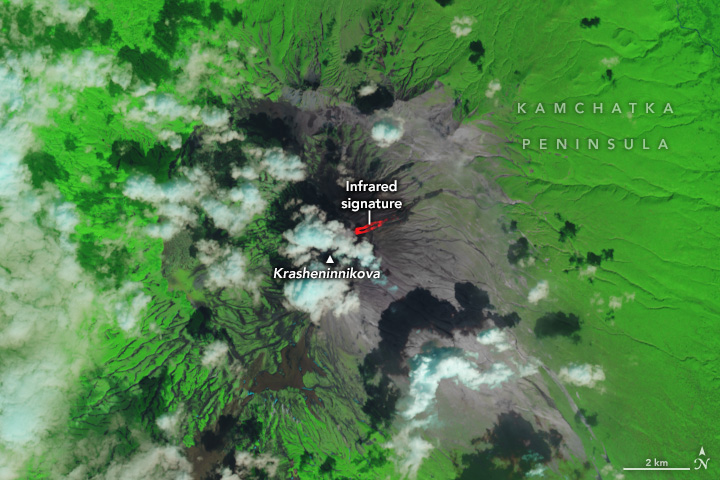

Volcanic activity detection

On August 2, ALS-2 also observed a notable quantity of displacement in Krasheninikova, a long-term volcano in the peninsula that broke out five days after the earthquake. The surface displacement measured the surface displacement (red in the insert on the above map) on the flank of the volcano, indicating that there was probably a dike of magma approaching the surface that day, according to Fielding. “If volcanologists had seen this data shortly after their acquisition, they could have recognized that an eruption was imminent.”

The Oli (Operational Land Imaging) on Landsat 8 captured an image (above) of a lava flow on the oriental flank of the volcano on August 25, 2025. The false color image describes the observations of infrared infrared light, almost infrared and visible (bands 7-5-4). The bright red indicates the infrared signature of the lava.

Judith Hubbard, structural geologist and co-author of Treamquake Insights, agreed that Instar was precious for volcanologists. “Insar is one of the main tools that scientists must understand volcanic activity,” she said. “With other types of data, such as gas emissions and seismological signals, it can be used to determine the threat level of a volcano.”

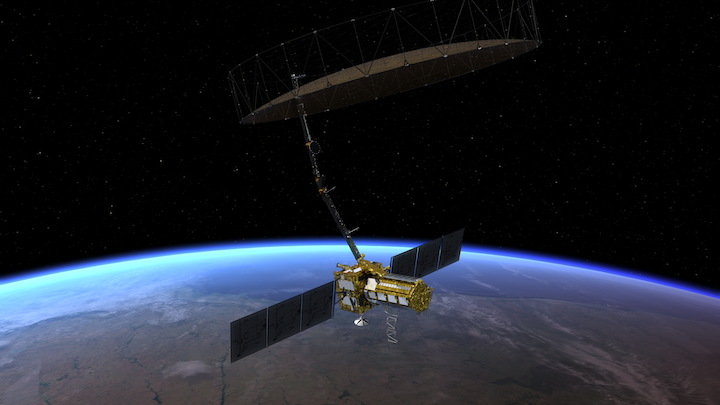

ARIA scientists have used ALOS-2 radar data and other satellites for several years, but the Nisar satellite (NASA-Isro synthetic radar), launched in July 2025, should open a new, more complete source of ISAR data for the mapping of travel after holes. “With Nisar, we will get better quality and more frequent movement cards from earthquakes, volcanoes, landslides and other processes that cause the surface of the earth,” said Fielding.

For earthquakes in highly wooded areas such as the northwest of the Pacific or Indonesia, the frequent nisar cover and the L-strip wavelength will provide displacement cards that were not at all available in other satellites, he added. When released, Nisar data products should be available in two days after observation, and even faster during the response to a disaster. An illustration of Nisar in orbit around the earth is above.

Images of the NASA land observatory by Wanmei Liang, using the data provided by the NASA Aria / JPL-Caltech team. The travel card is based on the Landsat data of the US Geological Survey and the ALOS-2 data of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (Jaxa). Nisar illustration of the Nisar project. History of Adam Voiland.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/Amelia-Earhart-100125-50b17dbbaaec4b58b416672da216e0be.jpg?w=390&resize=390,220&ssl=1)