A robotic underwater glider goes around the world

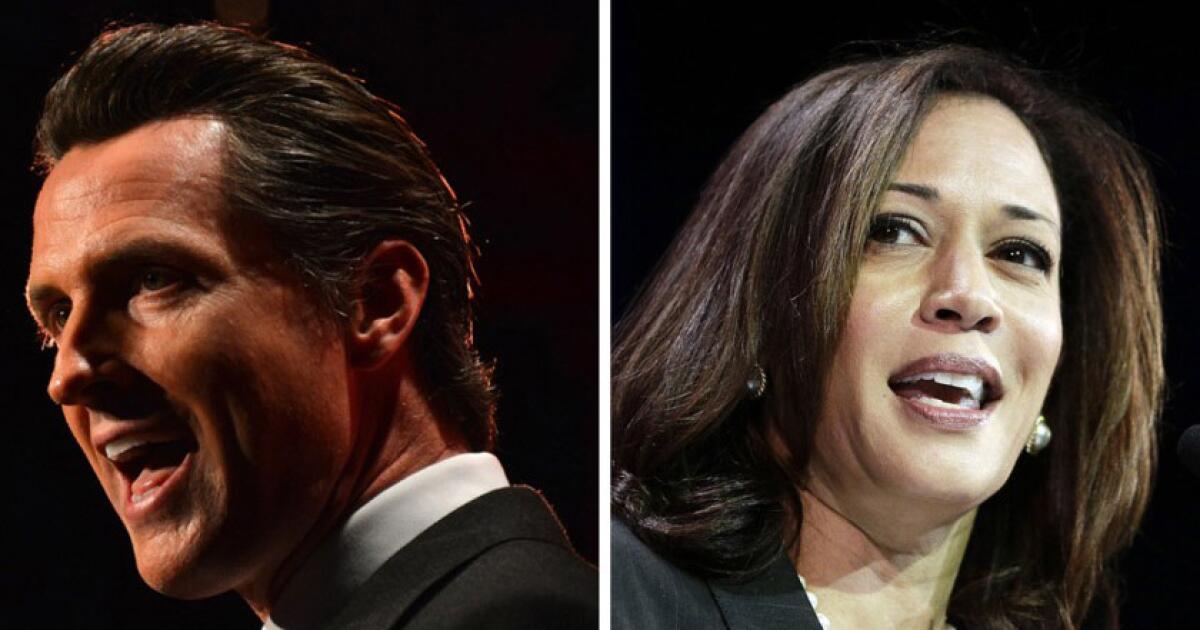

The Redwing glider during a test launch

Teledyne Marine

A small robot submarine is going around the world for the first time. Teledyne Marine and Rutgers University New Brunswick, New Jersey launch an underwater glider called Redwing as part of their Sentinel mission from Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts on October 11.

Researchers have been using underwater gliders since the 1990s. Rather than a propeller, the gliders have a buoyancy engine, a gas-filled piston that slightly changes the overall buoyancy of the craft. An electric motor pushes the piston to make the glider heavier than the water so it sinks slowly, descending at a shallow angle. Upon reaching the bottom of the dive, about 1,000 meters, the piston is removed and the submarine, now floating, slides upward. The result is slow, steady progress along a jagged path. Auxiliary propellers can be engaged if necessary, but the aim is to avoid this.

“Redwing will glide with the currents rather than fight them, moving at an average speed of 0.75 knots,” or just under 1 mile per hour, says Shea Quinn of Teledyne Marine, who is leading the Sentinel mission.

At 2.57 meters long, Redwing is no bigger than a surfboard, but weighs 171 kilograms. Previous gliders flew missions for months – the Redwing’s fuselage is filled with batteries, giving it even greater endurance.

“The historic Sentinel mission aims to complete its circumnavigation in approximately five years,” Brian Maguire of Teledyne Marine. Redwing will travel alone, followed by Teledyne Webb Research engineers and Rutgers University students, as it surfaces and communicates via satellite. Mission Control will adjust the glider’s heading twice daily to keep it on the projected flight path. During this five-year journey, the battery will likely need to be changed halfway, says Maguire.

Redwing will follow the route of explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s circumnavigation from 1519 to 1522, stopping at Gran Canaria off northwest Africa, the Cape in South Africa, Western Australia, New Zealand, the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic and eventually Brazil, before returning to Cape Cod, a journey of approximately 73,000 kilometers.

Gliders can carry out long-range, long-duration research missions without expensive support ships, and they have become essential for tracking data critical to understanding climate change. Redwing will collect data on ocean currents and sea temperatures in relatively unknown regions using a variety of instruments.

“We believe this is the most sustained deep sea sampling exercise ever undertaken,” says Maguire.

Previous glider missions crossed the Atlantic in 2009 and the Pacific in 2011, and traveled beneath the Ross Ice Shelf and other inaccessible locations. “Gliders are great tools for making measurements in areas too risky for a ship to dispatch – such as in the middle of a storm or hurricane, or in front of a calving glacier,” says Karen Heywood of the University of East Anglia in the UK. The main dangers to completing the mission will likely be fishing nets and shipping lanes rather than weather conditions. “Gliders are actually remarkably durable and are able to withstand high winds and rough seas,” she says.

Alexander Phillips of the UK’s National Oceanography Center says the glider will also face other dangers, including sharks and biofouling, in which plants and algae build up on the ship’s outer hull. “Biofouling can render a glider unusable due to marine growth on the outside of the glider. In some areas of the ocean, gliders have been lost to sharks. Shipping and fishing occasionally damage or result in the loss of gliders.”

Data from the mission will be shared with universities, schools and other institutions around the world, but the main goal is to showcase the gliders’ capabilities and inspire future missions.

Topics: