A resident of Martha’s Vineyard has kept a unique Jaws accessory by Steven Spielberg

Making a film is an intense experience. The average shooting takes about three months, and during this time, all the people involved rush to ensure that everyone and everyone is where they must be to obtain the photo, with all the other secondary considerations. In a working environment where each costume, accessory and together is as precious as possible to be used on the camera before being thrown, it is a wonder that everything is saved from a film shoot. However, of course, many small accessories, scripts and other trinkets are kept as memories. On occasion, some larger accessories or defined elements of great importance are also saved. Almost everything else is rightly supposed to be, possibly ransacked or lost.

However, from time to time, research appears in cinematographic ephemers that even the filmmakers supposed to disappear forever. This is what happened to Steven Spielberg during the visualization of the new exhibition “Jaws: The Exhibition” at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles. By her own admission, Spielberg was shocked to discover that someone had kept the ocean buoy of the film’s opening scene, and that she had thus survived 50 years later to be used as part of the exhibition. It turned out that the savior of the accessory was Lynn Murphy, a resident of Martha’s Vineyard who helped the “Jaws” crew with part of their shot on the water in 1974.

While “Jaws: The Exhibition” contains many pieces of accessories, notes, storyboards, camera equipment and memories of the manufacture of “Jaws”, this buoy is particularly emblematic of the way the film has been the chances of its famous shooting and has become one of the biggest and most influential films of all time.

Spielberg argues that collectors knew something “on the jaws hard to the test of time

According to the story that accompanies the museum’s buoy, Murphy “provided nautical equipment and” jaws “crew, and helped drive vehicles on the water, which included the towing of the Sadly mechanical shark without work. Apparently, Murphy decided to keep the buoy that the Watkins condemned Chrissia (Susan Backlinie) briefly holds during her shark attack. Murphy took care of the buoy at his home until 1988, when collector Erik Hollander discovered that he was still there and decided to acquire him himself. Apparently, the buoy has remained in the Hollander collection so far.

Spielberg himself was amazed that he was kept during all these years. As he explained during a press event for the exhibition to which this writer attended, it was incredulous that someone – anyone – can remember the buoy:

“Archives of collectors from all over the world who somehow knew something that I did not know … When we shot the opening scene of Chrissie Watkins taken by the shark and we had a buoy floating in the water, how did someone know to take the buoy and bring it home and sit on it for 50 years and then lend it to the academy?”

Spielberg certainly has a point. He then described how “Jaws” was a film that he and Universal Studios were really worried at some point would never be finished, and even less successful. Although Peter Benchley’s source novel was a bestseller when the film went before the cameras, it was not quite a feeling at the level of “Twilight” or “Harry Potter”, where a raised fans base already planned to keep and / or resell memories later. Of course, “Jaws” continued to make the story of the film, to break all kinds of records and to inadvertently create the successful summer film in the process. However, this happened months after filming, it was therefore premonitory to keep a memory of the whole.

The man who kept the buoy was also an inspiration for Quint

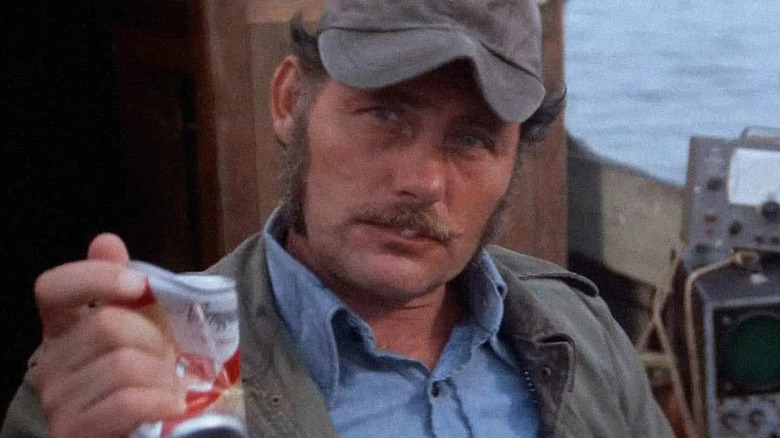

The answer to Spielberg’s question can be much simpler and healthier than the precognition of the success of “jaws”. Lynn Murphy was not only from the vineyard; He was also one of the men who inspired Quint’s representation by Robert Shaw. Most of the credit for Shaw’s indelible characterization for the captain of the ship obsessed with sharks tends to go to another native of Vineyard, Craig Kingsbury (who played Ben Gardner condemned in the final film). However, according to Matt Taylor, author of the book “Jaws: Memories from Martha’s Vineyard” (via the Vineyard Gazette), it is Murphy’s voice that Spielberg heard one day on the set and instantly decided that the cadence of Quint should correspond. Thus, Spielberg asked Shaw to look like Murphy, and the man who already worked as part of the film crew was represented on the camera as well.

So, even if Spielberg neither Murphy nor anyone else could have predicted that we are still talking in tones that respect “jaws” 50 years later, it is likely that he kept this buoy out of pride to be involved in the creative process of cinema. This feeling of contribution and belonging, to be part of a collaboration, is a great reason for the magic of the films. This magic, in turn, permeates objects such as costumes, accessories and other things matched with a greater resonance than they alone. A buoy is just a buoy, but, as all those who see “Jaws: The Exhibition” will say, this buoy is special.