Discover the first map of the seabed

Explore

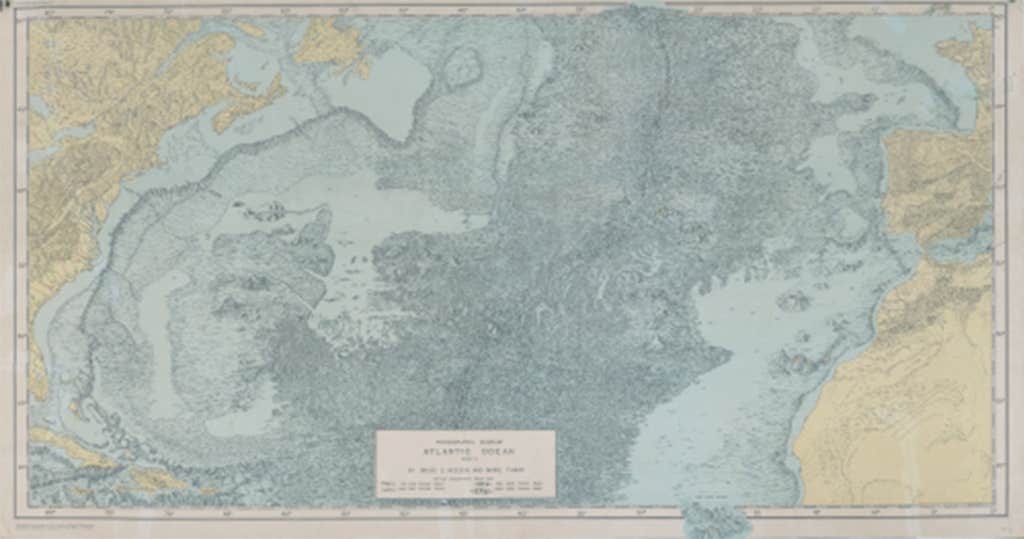

UNtil 1957, most of the public thought that the bottom of the ocean was an expanse of sand without flat affair, constantly extending worldwide. Then, the first relief card from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean highlighted its dynamic contours. That year, American scientists Marie Tharp and her longtime collaborator Bruce C. Heezen used Sonar data to trace, for the first time, the damaged land of the Atlantic floor, Root with ridges and ridges, painting valleys and many trays.

This map, shown here, was created in the style of a so-called physiographic diagram, which generally represents geological characteristics from above and on the side, as if it were seen from a small plane flying above the head. Although physiographic diagrams can instantly transmit the three -dimensional nature of an area, they are generally not useful for navigation. Due to the gaps in the data, the card created by Tharp and Heezen was also partially speculative. Tharp had to count on his training as a geologist to fill the whites, making illuminated assumptions on some of the exciting contours of the ridge of the Atlantic’s middle, dominating nearly 10,000 feet above the surrounding seabed; The Azores plateau, extending over around 2.2 million square miles; and a previously mysterious chain of submarines south of the Azores archipelago.

Tharp and Dezeen’s First Map of the Atlantic Seafloor Ultimately Played an Important Role in the Widespread Acceptance of the Theories of Plate Tectonics and Continental Drift, Which Were First proposed by Alfred Wegner in 1912. While Creating Their Map, Tharp and Dezeen Overlaid Seismic and Earthquake Data ONTO Their Diagram of Topography, Which Revealed That Many of the Globe’s Earthquakes Had Occurred Along the Mid Atlantic Ridge.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus members benefit from experience without advertising. Connect or join now.

Tharp and Heezen describe some of the difficulties of creating their card in their 1959 book, Ocean floors: I. The North Atlantic. When you make a map of a terrestrial landscape, the forms of the mountains and valleys are a “question of fact recorded”, they write, so the challenge is to choose the characteristics to be representing and which to leave aside. But at sea, a large part of the landscape is hidden under the breaststrokes, so there are many more conjectures.

The Cold War provided a motivation for the card style that Tharp and Dezeen have chosen to create, according to a recent blog of the Congress Library. A large part of the data on which they were based were classified, and the physiographical card was a means of transmitting this data approximately, without offering state secrets.

Tharp and Hezeen have created many other ocean floor cards over the years, using newly available data and filling the rest, with their imagination.

Image of lead: geography and cards division

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus members benefit from experience without advertising. Connect or join now.